Report

to/Rapport au :

Comité de l'urbanisme

and Council / et au Conseil

21 March 2011 / le 21 mars 2011

Submitted by/Soumis

par : Nancy Schepers, Deputy City

Manager, Directrice municipale adjointe, Planning

and Infrastructure, Services d'Urbanisme et d'Infrastructure

Contact Person/Personne-ressource : Richard Kilstrom,

Manager/Gestionnaire, Policy Development and Urban Design/Élaboration de la

politique et conception urbaine, Planning and Growth Management/Urbanisme et

Gestion de la croissance Élaboration de la politique et conception urbaine

(613) 580-2424

x22653, Richard.Kilstrom@ottawa.ca

|

SUBJECT: |

|

|

|

|

|

OBJET : |

AMÉNAGEMENTS INTERCALAIRES DE FAIBLE

HAUTEUR dans LES QUARTIERS bien établis |

REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS

That Planning Committee recommend

Council approve:

1.

An amendment to the Zoning By-law

2008-250 to include a new section which provides regulations for infill

development as detailed in Document 2;

2.

The Urban Design Guidelines for Low-Rise

Infill Housing as detailed in Document 3;

3.

The proposed changes to the City’s submission

requirements and procedures – including procedures and fees for new planting,

the Urban Tree Conservation By-law and the Drainage By-law as detailed in Document

4 and direct the appropriate branches to implement these changes within eight

months of Council approval of this report; and

4. The addition of one Full-Time Employee for the Forestry Services Branch

as a pressure to the draft 2013 budget, in order to ensure that the amendments

to the Urban Tree Conservation By-law can be implemented.

RECOMMANDATIONS DU

RAPPORT

Que le Comité de l’urbanisme recommande au

Conseil :

1.

approuve

une modification au règlement de zonage 2008-250 afin d’inclure un nouvel

article qui fournit une réglementation quant aux aménagements intercalaires,

comme il est expliqué en détail dans le document 2;

2.

d’approuver

les Directives d’esthétique urbaine pour les aménagements résidentiels

intercalaires de faible hauteur document 3 ci-joint;

3.

d’approuver

les modifications proposées aux exigences en matière de présentation des

demandes d’aménagement et aux procédures de la Ville - y compris les procédures

et les coûts de la nouvelle plantation, au Règlement municipal sur la

conservation des arbres urbains et au Règlement sur le drainage document 4

ci-joint et de demander aux services concernés d’adopter ces modifications dans

les huit mois suivant l’approbation du présent rapport par le Conseil; et

4.

Ajoute

un employé à temps plein à la Direction des services forestiers comme pression

du budget préliminaire de 2013 afin de veiller à ce que les modifications au

Règlement sur la conservation des arbres urbains puissent être mises en œuvre.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Low-rise infill housing is continually being built and is seen as a

beneficial addition to neighbourhoods as long as the infill is compatible and

makes a positive contribution to the neighbourhood. In Ottawa there are increasing amounts of

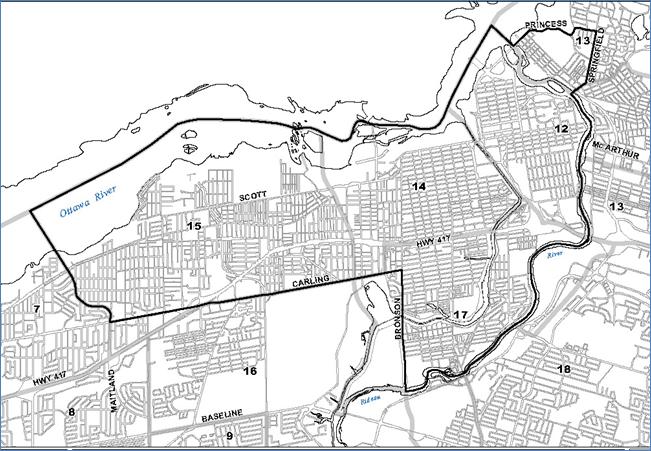

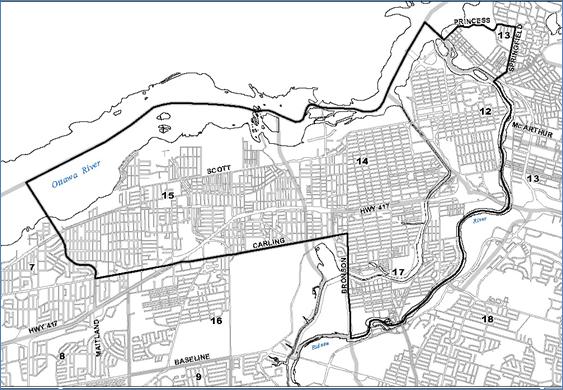

infill, in particular in Wards 12, 13, 14, 15 and 17, and, as certain

neighbourhoods in these wards are seen as very desirable, infill in these areas

is expected to continue. Although much

of this is positive, there are certain negative building patterns that have reduced

the compatibility of some infill in these wards.

This report is being brought forward in order to propose changes to

permissions and procedures related to infill housing that aim to increase the positive

contributions and improve the overall compatibility of low-rise infill development.

The proposed changes were developed following a long study period that

included an extensive visual survey of new infill construction, analysis of the

survey data, the creation and review of various options for change, and a

comprehensive internal and external consultation process.

A comprehensive stakeholder

consultation process began in early 2011.

The consultation process,

documented fully later in this report, included:

§ Four

public meetings held in February 2011 and one in September 2011

§ 17

meetings with industry and community stakeholders

§ Additional

meetings with individuals and interest groups as requested throughout the process

and ongoing email correspondence with stakeholders

The recommendations recognise the importance of low-rise

infill housing. They also acknowledge that

infill results in neighbourhood change and that this change must contribute

positively to the neighbourhood and not erode the characteristics that make the

neighbourhood liveable.

The purpose of the recommendations is to enhance the nature of new low-rise

residential development that is being built within stable residential

neighbourhoods. To ensure that infill makes a more positive contribution to the

character and quality of the neighbourhoods the recommendations include:

§ Changes

to the existing zoning by-law provisions (Document 2) as they relate to the

construction of new, low-rise infill housing with the study area (see Document 1)

§ Revisions

to the City’s current Urban Design Guidelines for Low-Rise Infill Housing

(Document 3 - applicable within the urban area only)

§ Changes

to City submission requirements and

procedures, the Urban Tree Conservation By-law and the Drainage By-law (Document

4 – applicable within the urban area only)

The recommendations are

expected to:

§ Improve

the relationship between the front of house and the street, and promote more

neighbourly frontages and uses at street level

§ Improve

the landscape and streetscape treatment so that new homes ‘fit’ better in

established neighbourhoods

§ Increase

the permeability of yards and front yard green potential

§ Improve

the implementation of the City’s Urban Tree Conservation By-law

§ Increase

the amount of information that the City receives with infill applications so

that it is possible to better evaluate the impact of proposed construction

§ Ensure

that infill lots are graded as per approved plans

§ Improve

internal communication and co-ordination related to infill applications within

and amongst municipal departments

§ Improve

the clarity of the Urban Design Guidelines for Low-Rise Infill Housing

§ Create

opportunities for good infill to be recognized

The recommendations will apply to Building Permit, Site Plan and

Committee of Adjustment applications submitted after Council approval of the

changes. The proposed changes related to

improved implementation of the Urban Tree Conservation By-law (as outlined in

Document 4) will require an additional staff resource. The remainder of the proposed changes have no

financial implications for the City.

Several follow up actions are being proposed, including an analysis of

the impacts of zoning by-law setback and height provisions on infill

development, a determination of whether the zoning by-law changes should be

applied to additional neighbourhoods outside the current study area, as well as

a complete review and monitoring of the currently proposed changes

(Recommendations 1 through 3 of this report).

RÉSUMÉ

On assiste

régulièrement à la mise en chantier d’aménagements résidentiels intercalaires

de faible hauteur. Ces aménagements sont réputés être un atout pour le

voisinage, dans la mesure où ils sont compatibles et apportent une contribution

positive aux quartiers dans lesquels ils sont bâtis. On compte de plus en plus

d’aménagements intercalaires à Ottawa, en particulier dans les quartiers 12,

13, 14, 15 et 17, et, comme ces quartiers sont très convoités pour leur

convivialité, on projette d’y poursuivre l’érection d’aménagements

intercalaires. Bien qu’on y trouve généralement des avantages, ces quartiers

comportent des modèles de construction dont les effets négatifs réduisent la compatibilité

de certains aménagements intercalaires.

Le présent rapport

propose de modifier les permissions et procédures reliées aux aménagements

résidentiels intercalaires, dans un secteur donné, afin d’accroître la contribution

positive et d’améliorer la compatibilité des aménagements intercalaires de

faible hauteur.

Les modifications

sont proposées à la lumière d’une longue période d’étude qui comportait une

vaste enquête visuelle des aménagements intercalaires nouvellement construits, l’analyse

des données de cette enquête, l’élaboration et l’examen de diverses solutions de

modification et un processus de consultation interne et externe.

Une consultation de tous les intervenants a été

amorcée en 2011. Ce processus de consultation, dont les détails figurent plus

loin dans le présent rapport, prévoyait :

§ Cinq réunions publiques dont quatre ont été tenues en

février 2011 et une en septembre 2011

§ Dix-sept réunions avec l’industrie et la collectivité

§ Des réunions supplémentaires, avec des personnes et

des groupes d’intérêt, dont la tenue s’est avérée nécessaire durant le

processus et une correspondance continue par courriel avec les divers

intervenants

Les

recommandations font état de l’importance des aménagements résidentiels

intercalaires de faible hauteur. Elles reconnaissent aussi qu’ils entraînent des

changements dans le voisinage et que ces changements doivent apporter une contribution

positive au voisinage et laisser intactes les caractéristiques qui favorisent

la qualité de vie du milieu.

L’objet de ces

recommandations est d’améliorer la nature des nouveaux aménagements

résidentiels intercalaires construits dans les quartiers résidentiels bien

établis. Voici ce qui est recommandé pour faire en sorte que ces aménagements

intercalaires contribuent au caractère et à la qualité des quartiers en

question :

§ Modification des dispositions actuelles du règlement

sur le zonage (document 2) qui traitent de la construction de nouveaux

aménagements résidentiels intercalaires de faible hauteur dans le secteur à

l’étude (document 1).

§ Révision de la version actuelle des Directives d’esthétique urbaine pour les

aménagements résidentiels intercalaires de faible hauteur (document 3

- ne s’applique qu’au secteur urbain).

§ Modification des exigences en matière de demande

d’aménagement et des procédures de

la Ville, du Règlement municipal sur la

conservation des arbres urbains et du Règlement sur le drainage (document 4

- ne s’applique qu’au secteur urbain).

Les recommandations visent à :

§ Harmoniser les façades de maison avec les rues en vue

de les rendre plus accueillantes.

§ Améliorer l’aménagement paysager et le paysage de rue

afin que les nouvelles demeures s’intègrent mieux dans le voisinage.

§ Accroître la perméabilité des cours et le potentiel

écologique des cours avant.

§ Assurer une mise en application rigoureuse du

Règlement municipal sur la conservation des arbres urbains.

§ Exiger des demandes d’aménagements intercalaires plus

étoffées afin que la Ville soit en mesure d’évaluer l’impact de la construction

proposée.

§ Assurer que les terrains destinés aux aménagements

intercalaires sont nivelés conformément aux plans approuvés.

§ Améliorer la communication interne et la coordination entre

les services municipaux qui traitent les demandes d’aménagements intercalaires.

§ Clarifier les Directives d’esthétique urbaine pour les

aménagements résidentiels intercalaires de faible hauteur.

§ Rechercher des occasions de souligner les aménagements

intercalaires réussis.

Les recommandations

s’appliqueront aux demandes de permis de construire et de plan d’implantation

ainsi qu’à celles soumises au Comité de dérogation une fois que le Conseil aura

approuvé les modifications. Les propositions exigeant une mise en application plus

étroite du Règlement municipal sur la conservation des arbres urbains (comme le

stipule le document 4) nécessiteront des ressources humaines

supplémentaires. Les autres modifications proposées n’ont pas de répercussion financière

sur les services de la Ville.

Plusieurs mesures de suivi

sont proposées, y compris une analyse des répercussions des dispositions du

Règlement de zonage concernant les retraits et la hauteur des immeubles sur les

aménagements intercalaires, une analyse de l’opportunité d’appliquer les

modifications au Règlement de zonage à des quartiers situés à l’extérieur du

secteur visé par l’étude, ainsi qu’un examen complet et une surveillance des

modifications projetées actuellement (recommandations 1 à 3 du présent rapport).

BACKGROUND

The Official Plan promotes intensification through a variety of ways,

one of which is infill development in the urban area. The Official Plan notes

that the stability and the character of established neighbourhoods is to be

ensured, and that these neighbourhoods have the potential for smaller scale

growth over time. While infill development will be different from the original

homes, infill proposed within the interior of established stable neighbourhoods

must be designed to complement and contribute to the area’s pattern of built

form, as well as its desirable landscape and streetscape characteristics.

In the spring of 2010 a number of community associations and individual

community members expressed concerns that recent, low-rise, infill housing

projects in their neighbourhoods were incompatible with the character of the

neighbourhood and were making a negative contribution to the community.

To better understand the issues, staff assembled a list of building

permits issued for infill detached, semi-detached, multiple attached dwellings

and stacked dwellings between January 2005 and the end of June 2010 in Wards

12, 13, 14, 15 and 17.

Many of the neighbourhoods in these wards were developed pre-war, are stable

and well established, have a distinctive character, and are seeing the largest

amount of low-rise infill. During the

summer of 2010, staff conducted a visual survey of over 400 properties on the

list. The survey found that there are

certain types and patterns of infill housing that appear to have a negative

impact on the landscape and streetscape character of neighbourhoods. The detailed survey findings are available on

the study web pages at ottawa.ca/infill. Based on the survey, staff began to work with

other City Branches and Departments to explore possible solutions to address

the identified issues.

At the same time, following from the October 4, 2010 report to Planning Committee Status of Urban Infill Development: Design Guidelines and Zoning By-law ACS2010‑ICS-PGM-0185, Planning and Growth Management staff was directed examine issues related to infill housing and report back to Committee.

DISCUSSION

The

recommendations, as detailed below and in the attached documents, are proposed

in order to:

§ Address

concerns over the impacts of infill housing and enhance the contribution of new

construction to streetscapes and neighbourhoods.

§ Improve

the clarity of policy documents so that they may be applied more effectively

§ Increase

and improve the level of information given to the City, thereby facilitating

the review of applications and providing the applicant with more clarity

surrounding City expectations.

§ Improve

the internal co-ordination of information so that applications can be reviewed

more effectively.

§ Ensure

that City assets in the right-of-way are identified and better protected.

§ Address

on-going concerns within this report’s study area, and in neighbourhoods that

fall outside the study area.

§ Monitor

and evaluate the impact of the proposed changes, and determine whether

additional measures are necessary.

Through the study

process, numerous ways of addressing areas of concern were considered. Detailed information on the study web pages ottawa.ca/infill outlines

a set of initial ideas that were considered by staff and put forward for public

feedback at the February 2011 consultation sessions. The ideas were informed by best practices in

other municipalities such as Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Toronto, Oakville

and Mississauga. Based on a vetting of the

ideas and options gathered from the February meetings, and on a process of

internal consultation with the affected branches and departments, the initial

set of ideas was refined into a second document that was released in early

September 2011 and discussed at the September public meeting. The September consultation document is also available

at ottawa.ca/infill. Based on participant feedback and through a

process of internal consultation, the ideas were refined to those presented in Documents

2, 3 and 4.

All of the changes to the permissions around

infill construction are encompassed by recommendations 1, 2 and 3, and detailed

in the associated Documents 2, 3 and 4 respectively. The rationale behind the changes proposed by

recommendations 1, 2, and 3 is explained in the three following sections.

Recommendation 1 - Changes to the Zoning By-law

within the Study area (Document 2)

Through the study,

there was recognition that

certain undesirable infill conditions would not change if there are no changes

to certain provisions in the Zoning By-law.

As such, recommendation 1 suggests changes to the Zoning By-law to lots:

§ within the R1, R2, R3 or R4 zones shown on the schedules in Documents 1

and 2; and,

§ on which a new residential building containing a detached,

semi-detached, linked‑detached, duplex, three unit or multiple attached

dwelling is constructed.

Specific changes being recommended (and detailed in Document 2)

include:

§ A new definition of grade,

based on the pre-alteration site grades, and a requirement to

confirm that grade is built as approved.

§ A

limit on the height and square footage of rooftop projection used to access roof

top patios.

§ A

calculation of front-yard setback based on the average of the adjacent homes.

§ Permission

for front-yard projections to be the average of those of the adjacent homes.

§ Permission

to build without offering on-site parking.

§ Permission

for front-yard parking (new infill only and with limits on hard surface area).

§ Restrictions

on hard surface area in the front-yard.

§ Restrictions

on the provision of front garages.

As noted in the October 4, 2010 report to Planning Committee, “applications

for infill development typically fall into two categories: those where some

form of planning review and public consultation is part of an application…and

those where no planning review occurs and the only application required is for

a Building Permit”.

For applications where only a Building Permit is required, the

applicable planning document is the Zoning By-law. Urban Design Guidelines are not applicable

law and cannot be included in the technical review done by the Building Code

Services Branch under the Building Code

Act. Thus, the Zoning By-law is the

sole tool to regulate built form for those applications that do not require

Site Plan Control and/or Minor Variances.

For applications that require Minor Variances or Site Plan Control

Approval, the Zoning By-law and the City’s Urban Design Guidelines can be

applied during the review process. However,

in cases where a proposed site plan is in complete conformity with the Zoning

By-law, the legal opinion is that the as-of-right permission as conferred by

the Zoning By-law would ultimately carry more weight before the Ontario

Municipal Board than would the Design Guidelines. The Committee of Adjustment has regard to the

Guidelines where applicable but the extent to which they may influence a

decision can relate directly to the extent to which they are raised at the

Hearing. Given the above, zoning

is the proper tool to affect the desired changes to low-rise infill housing.

Document 2 is the final

product of extensive internal and external consultation processes, and outlines

the proposed zoning changes. Endnotes in the Guidelines explain the

intent behind the proposed changes and are included to facilitate and clarify future

interpretation of the by-law provisions.

The changes take an approach to zoning that is more contextual than the

existing Zoning By-law 2008-250 provisions permit. The goal of this approach is to achieve

future infill development that is more sensitive to the characteristics of the

neighbourhood in which it is built.

Staff will monitor the results of the proposed changes to determine

whether the resulting infill is making the desired positive contribution to

neighbourhoods. This will include

monitoring of the uptake on the ‘no parking required’ provision and any

resulting potential impacts on street parking. If deemed necessary, the Department will undertake a study of the

on-street parking permit program within the study area, in order to determine

if existing programs should be expanded or new ones instituted.

As part of the examination of best practices, staff examined the

standards of other jurisdictions. By way

of an example, elements of the City of Toronto Zoning By-law 1156-2010, the

City of Ottawa Zoning By-law 2008-250, and the proposed zoning changes outlined

in Document 2 are compared in Document 5.

From Document 5, it is evident that the City of Ottawa’s current and

proposed regulations are more permissive than Toronto. Monitoring the impacts of the proposed

changes will help to determine whether additional and more restrictive zoning changes

are required, and/or if all forms of low-rise infill should be subject to Site

Plan Control.

Recommendation 2 - Changes to Urban Design Guidelines for Low-Rise

Infill Housing (Document 3)

Through the consultation it was clearly noted that, in many situations,

the Urban Design Guidelines for Infill Housing hold no weight and/or cannot be

applied. This is true of any application

that only requires a Building Permit to proceed. The Guidelines may be applied through the

Committee of Adjustment. However, it is

only when an application goes through Site Plan Control that the Guidelines may

be more judiciously applied. Given the

limited weight of the Guidelines, this study did not focus on significant

content changes.

Instead, the Infill Design Guidelines have been revised in order to

reduce the repetition in the document, clarify wording, improve the photo

examples and reorganise the information within headings and under new

ones. The Infill Design Guidelines have

also been revised so that the text reflects the proposed zoning changes coming

from the Infill Study. The new document Urban Design Guidelines for Low-Rise Infill Housing

(Document 3) is applicable to all urban areas of the city and replaces

the Urban Design Guidelines for

Low-Medium Density Housing - 2009 Update.

Recommendation 3 - Changes to City submission requirements and procedures,

the Urban Tree Conservation By-law and the Drainage By-law (Document

4)

Document 4 outlines a series of changes to procedures and submission

requirements aimed at improving internal co-ordination and communication, and

positively impacting the infill process and final product. For instance, more

detailed information in the submission packages will assist the City to more

fully understand the development that is being proposed, and whether all by-law

requirements are being met (e.g. zoning, private approach, and encroachment

by-laws). Early internal coordination

and review of the more detailed information may reduce the number of neighbour

complaints that require staff time to investigate, as well as the incidence of

By-law infractions that require later follow up, thereby saving the City time. Further, Document 4 also includes two initiatives

aimed at promoting open consultation and sensitive design. Staff

will create and provide an on-line consultation template for

builders/developers. The template will

outline a consultation process that builders/developers could follow in order

to enhance communication about a project with the immediate neighbours and the

neighbourhood. Staff will also create a

Low-Rise Infill Housing Award category for the next cycle of the City’s Urban

Design Awards program.

An amendment to the Drainage By-law is also being proposed to require

certification of final grade, which will help to address current problems where

site grading is not installed as per approved plans and should reduce requirements

for mid- and post-construction staff review and follow-up.

The impact of infill development on trees is significant, and as such, Document

4 outlines new information requirements meant to improve the implementation of

the current Urban tree Conservation By-law, which applies to all trees 50cm DBH

and greater on the subject lot and on adjacent lots. It does not, however, suggest a change in the

size of tree subject to the Urban By-law. To realize the changes outlined in

Document 4, one additional FTE Forestry staff position is required and will be

added as a 2013 budget pressure. Until

the approval of the proposed position, the Urban Tree Conservation By-law will

be implemented as it is currently.

While previous drafts of the document released in September 2011

proposed more rigorous attention to the impacts of development on trees on

adjacent lots - specifically, that on adjacent lots, trees 10 cm DBH (diameter

at breast height) or greater be documented and subject to Forestry staff review

- it was determined that the requirements of the Urban Tree Conservation By-law

had to apply equally to all lots and all trees; meaning that a 10cm DBH

standard could not apply on one lot while a 50cm DBH (currently the standard in

the Urban Tree Conservation By-law) applied to the subject infill lot. Forestry Services indicated that they did not

have the resources to expand the applicability of the Urban Tree Conservation

By-law to trees that are less than 50cm DBH, and that an expansion of the

applicability of the by-law would require a significant addition of staff

resources.

To ensure that new street trees are planted and properly maintained

when new infill lots are created, Document 4 also outlines a new tree planting

fee, to be charged to all building permit applications for each new single detached,

semi-detached, duplex and triplex unit not subject to Site Plan Control or Plan

of Subdivision. Forestry Services would

oversee the administration of this new tree planting requirement to ensure that

the appropriate species is selected, planted to optimum specifications, and

properly maintained for two years. As

such, this recommendation relieves developers of the requirement to enter into

development agreements with the City, of the need to have planting

specifications approved by Forestry Services, and of the two year maintenance

responsibility.

The changes outlined in Document 4 are applicable to all urban areas of

the city, not only those within the boundaries of the Study of Low-Rise Infill

Housing in Mature Neighbourhoods. As the

Document 4 changes do not deal with questions of neighbourhood character, but rather

with improved procedures, they can be applied without detailed neighbourhood

studies. The changes will help to

improve the residential infill process, and their benefits are seen as being

important to all urban wards.

PROPOSED FOLLOW

UP TO THIS REPORT

§ Within

one year of approval of this report, staff will complete a study that looks at

the zoning provisions related to

building height and setbacks in the R1, R2, R3 and R4 zones in the study area. The study will determine if additional

changes are required to improve the compatibility of new infill.

§ Within two years of approval of this report, staff

will determine whether the Zoning By-law changes brought forward in this report

should be applied, in whole or in part, to other areas of the city that are

subject to increasing low-rise infill housing.

§ Staff will monitor the changes resulting from

recommendations 1, 2, and 3 and, within three years of approval of this report,

undertake a complete review of the low-rise infill within the study area built

under the new changes.

RURAL IMPLICATION

There are no rural implications.

CONSULTATION

A comprehensive stakeholder consultation process began in early 2011. The record of this process is presented below.

A project information

meeting for industry

stakeholders was held in late January 2011.

Invitations to this meeting were sent to builders, developers,

architects and planning consultants involved in the construction of low-rise infill

housing. The stakeholders were asked to

circulate the invitation to industry colleagues who were not on the City’s

initial list. The January meeting was

attended by 30 industry members.

Resulting from the meeting, a group of ten individuals stepped forward

to form an Industry Working Group to liaise with the City. In order to better represent their industry

colleagues, the Working Group expanded to 16 members in September 2011. Over the course of this study, the City has

held nine meetings and working sessions with the Industry Working Group.

Four public meetings were held in February 2011. These were advertised via Public Service

Announcements, through the City’s website, as well as through communication

with the affected Ward Councillors and community associations.

The public meetings all followed the same format. Staff began by presenting a summary of the

findings of the survey on infill housing and followed this with a range of

possible ways to address negative current low-rise infill trends. Following the first meeting, all of the

findings and possible solutions were posted to the project web pages and can be

accessed at ottawa.ca/infill. The

staff presentation was followed by a question and answer period, and then a working

session where attendees were asked to provide feedback on the City’s ideas, and

to identify issues related to low-rise infill housing. The meeting attendance sheets were signed by

over 250 people. In addition to the

meeting working session, the City accepted input from stakeholders via email,

fax and letter up until March 16, 2011. A

record of the significant level of participation and feedback was circulated to

all attendees and also posted to the project web pages ottawa.ca/infill.

In May of 2011, staff

invited representatives from all of the registered community associations

within the study area to a meeting in order to discuss the study. The purpose was to engage the community

associations, and also to provide the associations with an opportunity to come

together; ten community associations accepted the invitation.

Over the course of this study, the City has held two working sessions

with the representatives of the community associations that elected to become

involved in the study. Staff also met

with the community associations individually upon request.

Over the course of the study, there were two joint meetings between the

Industry Working Group and the community association representatives. The

purpose of these joint meetings was to have the two groups meet and better

understand the issues that each is dealing with.

A public meeting was held at City Hall in

September 2011. This meeting was advertised

in two local newspapers, on the project web site, through the ward councillors,

and via email to all public and industry stakeholders. Over 70 people signed the meeting attendance

sheet. Staff presented a previously

released draft of the proposed changes to infill construction within the study

area. This was followed by a question

and answer period where the public were able to address senior managers in

attendance. Staff accepted comments on

the proposed changes up until the end of September 2011. A summary of the participation and feedback

was released to attendees and stakeholders in October. The information presented at the September

meeting and a record of the feedback was posted to the project web pages and is

available at ottawa.ca/infill.

Following the September meeting and information release, staff held a

number of internal and external meetings to further refine the proposed

changes. The ‘final’ proposed changes

were released to the Industry Working Group and community association representatives

for review in March 2012.

Throughout the process of this study, staff accepted input from

stakeholders and endeavoured to provide stakeholders with email updates of the

study progress.

As noted above, staff met with the community associations individually

upon request. Through these

meetings important neighbourhood concerns were identified and this study has endeavoured

to deal with them. However, due to its proximity to the University of

Ottawa, Sandy Hill has particularly unique concerns specific to infill student

housing. In the winter of 2012, Action

Sandy Hill raised the issue of single infill houses being created to house

large numbers of students (e.g. four apartments and upwards of 20 bedrooms per

house). Within Sandy Hill, such houses have

been created by working around the Site Plan Control process and therefore,

questions such as parking and garbage storage were not addressed. As this situation appears to be unique to

this area, and as the Infill Study does not address issues such as number of

occupants or interior uses of buildings, properly addressing the Action Sandy

Hill concerns would require additional study.

Complete details of the public consultation are posted at ottawa.ca/infill. The

document Record of Public Input, available

on ottawa.ca/infill, outlines all of the information presented at the February

2011 meetings. It also includes a

completed record of the public response to the information presented by the

City and additionally identifies all of the other issues of concern raised by

stakeholders at the sessions. Proposed changes (September 2011)

identifies all of the changes to by-laws and procedures that the City presented

at a September 2011 public meeting. The

document Summary of Stakeholder Input

(October 2011) outlines the stakeholder response to the City’s September

2011 document and meeting.

COMMENTS BY THE WARD COUNCILLORS

Councillor Chernushenko –

Capital Ward: I am fully in support of the excellent work

and thoughtful recommendations contained in this report, which comes on the heels

of extensive consultations, including with the public, community associations

and developers.

However, there is one recommendation that I feel is missing from this

report, and which I may decide to address through a motion at Committee. I

believe that it is appropriate and necessary to restrict front yard parking to

lots with a minimum width of at least 5.6 metres. This would prevent excessive

curb cuts (which eliminate the traffic calming effect of on-street parking) and

would be an important measure for saving mature urban trees, preserving

permeable and natural front yards and keeping cars out of front yards.

Obviously, some larger and thornier problems also remain to be

addressed (e.g. inappropriate building height, mass and scale) which will have

to be dealt with in the not-too-distant future.

Councillor Hobbs – Kitchissippi Ward: I am in full support of this report, and am pleased to see it coming forward after almost two years of work on infill issues. The changes proposed to the Zoning By-Law and the Urban Design Guidelines will deliver more compatible development to our urban neighbourhoods right away. By making these changes part of the Zoning By-Law rather than just guidelines, this will ensure properties that do not require a minor variance or rezoning will also be more compatible. While some of the changes are not perfect, they do represent a balanced solution to a basket of problems that were not consistent across the city or even across my own ward. The direction to monitor the results of the changes and undertake a review within three years of Council approval is ideal as it will serve to provide a better guide for what further refinements should take place.

I am especially thrilled with the improvements to the Urban Tree Conservation By-Law which will give the City the force it needs to save more mature trees that are one of the reason people are choosing to raise their families in mature neighbourhoods in the first place. This is why it is so important that we approve the budget for one FTE for the Forestry Services Branch.

I would like to thank the entire Planning and Growth Management team that worked to help improve the way our urban wards intensify.

Councillor Fleury is aware of this report.

Councillor Clark is aware of this report.

Councillor Holmes is aware of this report.

LEGAL IMPLICATIONS

The Planning Act requires that approval authorities such as the Council, staff through delegated authority, the Committee of Adjustment or the Ontario Municipal Board have regard for relevant policy documents such as design guidelines. Thus, such documents, while they are to be considered, are not binding and can only be applied if there is an application under the Planning Act. As discussed above, if all that is required is a Building Permit, the Chief Building Official does not have the legal ability to apply such documents.

Therefore, to ensure that the principles contained in design guidelines are applied where site plan, subdivision or Committee of Adjustment approval is not required, it is necessary to incorporate such principles into the Zoning By-law

RISK MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

No risks have been identified.

FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS

Recommendations 1 and 2: There are no direct financial implications.

Recommendation 3: The proposed new tree planting fee revenues will fund

tree planting costs. It is anticipated that there will be no net financial impact.

Recommendation 4: The FTE, and associated funding, for the additional

position in the Forestry Services branch will be brought forward as a budget

pressure through the 2013 budget process.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS

The new procedures related to the documentation of existing trees (see Document 4) are expected to improve the implementation of the Urban Tree Conservation By-Law, which will, in turn, support the City’s urban forestry policies and percentage tree cover targets.

ACCESSIBILITY IMPACTS

There are no implications from an accessibility perspective.

TECHNOLOGY IMPLICATIONS

There are no direct technical implications associated with this report.

CITY STRATEGIC PLAN

This study supports the following

priorities and objectives of the Strategic Plan.

F1- Become leading edge in community and urban design including housing creation for those in the city living on low incomes and residents at large

F2 – Respect the existing urban fabric, neighbourhood form and the limits of existing hard services, so that new growth is integrated seamlessly with established communities

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION

Document 1 Map of Study Area

Document 2 Zoning By-law changes, for R1, R2, R3 and R4 zones, within the study area

Document 3 Urban Design Guidelines for Low-Rise Infill Housing

Document 4 Changes to City submission requirements and

procedures, the Urban Tree Conservation By-law and the Drainage By-law

Document 5 Comparison of City of Toronto Zoning By-law 1156-2010, the City of Ottawa ZBL 2008-250, and Document 2

DISPOSITION

Planning and Growth Management Department to undertake the follow-up

implementation measures that are its responsibility:

§ Legislative and Technical Services Unit to

prepare the by-law adopting the Zoning By-law Amendments, forward to Legal

Services, and undertake the statutory notification

§ Notify persons who made oral or written

submissions at Planning Committee and all persons and public bodies who

requested to be notified of the amendments.

§ Community

Planning and Urban Design Unit to e-publish the Urban Design Guidelines for

Low-Rise Infill Housing and notify all affected City departments

§ Community

Planning and Urban Design, assisted by other departments as required, to implement

the actions and changes outlined in Document 4

Planning and Growth Management Department to undertake the following as

a follow up to this report:

§ Complete a study, within one year of Council

approval of this report, of the zoning provisions related to building height

and setbacks in the R1, R2, R3 and R4 zones in the study area, to determine if

additional changes are required to improve the compatibility of new infill;

§ Within two years, determine if the Zoning By-law

changes brought forward in this report should be applied, in whole or in part,

to other areas of the city that are subject to increasing low-rise infill

housing; and

§ Monitor the results of the changes resulting from

recommendations 1, 2 and 3; and to, within three years of Council approval of

this report, undertake a complete review of all infill within the study area

built under the new changes.

Public Works Department to undertake the follow-up implementation measures

that are its responsibility:

§ Forestry Services to prepare the by-law

adopting the Urban Tree Conservation By-law Amendments, forward to Legal

Services, and undertake any statutory notification

§ Forestry Services to add one FTE as a budget

pressure for 2013.

Environmental Services Department to undertake the follow-up

implementation measures that are its responsibility:

§ Prepare the by-law adopting the Drainage

By-law Amendments, forward to Legal Services, and undertake any necessary

statutory notification.

City Clerk and Solicitor’s Department to forward all implementing

by-laws to City Council.

Endnotes:

(1) The

identified area was the subject of a visual survey of infill housing in the

summer of 2010. Many of the

neighbourhoods were developed pre-war, are well established and have a

distinctive character. They are also

seeing the largest amount of low-rise infill within the City. To conduct the survey, the City assembled a

list of building permits issued for low-rise residential infill between January

2005 and the end of June, 2010. This amounted to over 400 properties; these

were visited and photographed. Although

there is community interest in expanding the area of application, the City

believes that prior to study of the infill patterns in the neighbourhoods, it

is impossible to extend the area of application.

(2)

The majority of the neighbourhoods within the study

area were developed without attached front garages or with front garages that

take up a limited percentage of the total lot frontage. This means that the

greater percentage of the frontage is devoted to built form that includes

doors, windows, porches and stoops that create a positive relationship between

the structure and the street; as compared to blank garage doors which have a

poor interface with the street. This

poor condition becomes exacerbated as lots become narrower and more

constrained. Removal

of a garage or carport in favour of other parking solutions is meant to

encourage improvements to the interface between ground floor and street

activity. By removing the garage or

carport door, the potential exists to create street-facing, ground floor living

space in its place.

Note

that a garage constructed on a corner side frontage, or detached and at the

rear of the property is permitted to have doors facing the street.

(3)

This provision addresses the case where a driveway/

parking spot is at the side or rear and does not provide access to a front

door. The intent behind the provision is to allow access to a front door but to

ensure that the hard surface walkway is not wide enough to park on and to

maintain a large percentage of soft surface area in the front yard.

(4)

The intention behind allowing front yard parking

is to provide more options around how and where cars can be stored on a

lot. In certain instances and in certain

neighbourhoods, front yard parking is seen as more desirable than an attached

garage or carport because, allowing for front yard parking can permit a

building façade that is more in keeping with established character of the

neighbourhoods in question. In

comparison to driveway access to rear yard parking, front yard parking can

reduce the amount of paved area on a lot and thereby provide more potential for

contributions to surface water infiltration.

Where the designer/builder selects to build the driveway/ parking

spot/walkway using permeable surfaces, there will be further contributions to

surface water infiltration.

(5)

In the Zoning By-law, the minimum length of a

parking spot is 5.2 meters. The

provision allows front yard parking spots from 5.2 – 6.0 meters in length. The longer lengths are permitted so that situations

where cars overhang the sidewalk or curb can be avoided. Where there is a narrow distance between the

property line and curb or sidewalk, the length of the spot should be increased

beyond the 5.2 meter minimum.

(6) There are

neighbourhoods where the existing and dominant front yard setback depth is

greater than what is permitted in the current Zoning By-law and where the

by-law permissions are not reflective of the pattern and character of the

neighbourhood. The intention of this

provision is to take a contextual approach to establishing setback in order to

ensure greater compatibility between the front yard setbacks of infill and

existing homes, and to allow for projections such as porches that would also reflect

established character.

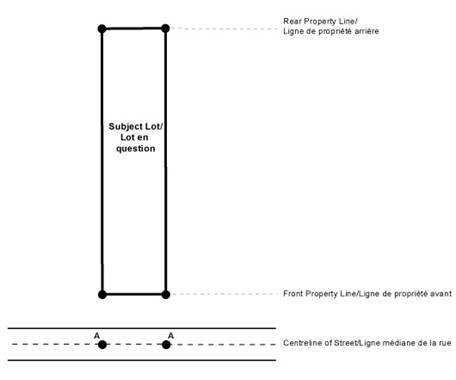

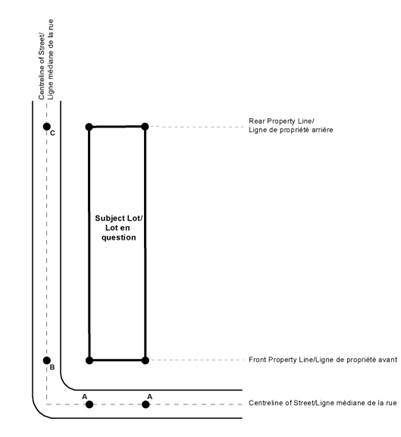

(7) The manipulation of site grading can lead to

significant grade differences between the infill and surrounding lots. The overall building height should reflect

the prevailing context of neighbouring buildings, with a maximum height limit

identified in the applicable zoning by-law; the intention behind the new

definition of grade is to ensure that this occurs on a more regular basis.

The current definition of grade is ambiguous as it does not indicate

where grade is to be measured or how many points must be included in the

calculation.

The new proposed definition is based on known and static points that can

be measured and would not change based on the proposed placement of a building

on a lot or with the shape of a building footprint. The new definition provides clarity with

regards to the number of points required in the calculation and where these are

to be taken.

A calculation based on points on the property line should result in less

chance of site alteration, and thus more chance that site grades will reflect

adjacent lots. A calculation that

includes points on the street centreline, should also ensure that the grade

calculation is reflective of the immediate context.

(8)

Projections above the building height limit have

the potential for adverse impacts of overlook and privacy, as well as access to

sunlight. However, projections which

provide access to a roof decks are permitted as of right in the Zoning

By-law. Currently, the Zoning By-law

does not specify the permitted area, the permitted height or a definition of

what constitutes habitable space. The

intent behind the new provisions is to add direction to what is permitted with

regards to projections which provide access to roof decks. The provisions continue to permit projections

but require that these focus on serving the intended function, which is to

provide access, but not more.

(9)

Chimneys are exempt from the height limit.

TABLE OF

CONTENTS

Ottawa

by Design

1.0

Introduction

1.1 Purpose and Objectives

1.2 The Official Plan

1.3

Intensification

1.4 When are Design Guidelines applied?

2.0

Streetscapes

3.0

Landscape

4.0

Building Design (Built Form)

4.1 Siting

4.2 Mass/Height

4.3 Architectural Style and Facades

5.0

Parking & Garages

6.0

Heritage Building Alterations/Additions

7.0

Service Elements

8.0

Infill on Narrow Lots

9.0

Glossary

10.0

Appendix: How Design Guidelines fit with the current Development Approval

process

1.0 Introduction

This is a series of design guidelines for

infill housing to help fulfill some of the design strategies for Ottawa as

outlined in the Official Plan. It is intended as a basic framework for the

physical layout, massing, functioning and relationships of infill buildings to

their neighbours.

Infill housing is

about the development of vacant lots or portions of vacant lots in established

urban areas. A vacant lot may have been

vacant historically, created by a severance, or result from demolition, fire

and/or some other means. Infill optimizes the efficient use of serviced lands

adjacent to existing infrastructure and transportation modes. Design guidelines

are a working tool to help developers,

designers, property owners, utility providers, community groups,

builders, Council and City staff implement policies of the Official Plan and

facilitate the approvals process by highlighting the desired type of

development. Applicants are encouraged to use the guidelines to come up with ideas to

further improve urban infill. Note that

not all of the individual design guidelines listed in this document apply or

are appropriate in every infill situation and thus, the guidelines are not to

be used as a checklist in evaluating proposals.

Well-designed

residential infill projects can integrate harmoniously into a local landscape,

improving and enriching a neighbourhood, and increasing the value of the infill

development itself. Good design is critical to growing cities and essential for

increasing densities appropriately. The keys to good infill are recognizing the

scale and visual lot pattern of the desirable neighbourhoods that exist, and

those planned for the future, and not permitting the car to dominate the public

realm. Designing for the needs of pedestrians and cyclists, and integrating the

car appropriately into a planned urban environment, improves the quality of the

city streetscape and helps create liveable cities.

Liveable communities consist of a balanced

environment where pedestrians, cyclists and automobiles exist supportively

together to create a sense of place and local identity.

These guidelines target those attributes that

can guide various stakeholders into achieving quality design for infill

development with regard to:

§

Public

streetscapes

§

Landscape

§

Building

design

§

Parking

and garages

§

Heritage

building alterations/additions

§

Service

elements

1.1 Purpose

and Objectives

In general, the aim of the guidelines is to

help create infill development that will:

§

Enhance

streetscapes

§

Support

and extend established landscaping

§

Be

a more compact urban form to consume less land and natural resources

§

Achieve

a good fit into an existing neighbourhood, respecting its character, and its architectural

and landscape heritage

§

Provide

new housing designs that offer variety, quality and a sense of identity

§

Emphasize

front doors and windows rather than garages

§

Include

more soft landscaping and less asphalt in front yards

§

Create

at grade living spaces that promote interaction with the street

§

Incorporate

environmental innovation and sustainability

In so doing, these design guidelines

highlight the important elements of building in a civic-minded spirit.

Pursuing a comprehensive design strategy,

entitled ‘Ottawa by Design’, these guidelines serve to fulfill the Official

Plan’s objectives in the area of community design.

The Plan directs growth to established areas,

to maximize the use of land that is already serviced, accessible and close to

existing amenities. Intensifying empty lots with infill development will become

a more common occurrence, and good design will be the essential ingredient for

achieving quality development at higher densities.

The guidelines are intended to address the

small-scale changes in a neighbourhood, but are also meant to deal with more

substantive changes to achieve a good ‘fit’ within an established context.

Design direction is offered to assist people

who are proposing change and also help those evaluating proposals through the

development review process, to assess, promote, and achieve appropriate infill.

In addition, neighbourhood residents and interested stakeholders can see what

the expectations are for infill development, and thereby obtain a better

understanding of how development proposals will be evaluated.

To facilitate the approvals process, builders

can get practical ideas and guidance on important design ingredients for

building in established communities prior to starting the design of their

project.

1.2 The Official Plan

“The

Design Objectives of this Plan are qualitative statements of how the City wants

to influence the built environment as the city matures and evolves. These

Design Objectives are broadly stated, and are to be applied within all land use

designations, either at city-wide level or on a site-specific basis.” (Excerpt

from the Official Plan)

Design Objectives (Section 2.5.1 of

the Official Plan)

- To

enhance the sense of community by creating and maintaining places with

their own distinct identity

- To

define quality public and private spaces through development

- To

create places that are safe, accessible and are easy to get to, and move

through

- To

ensure that new development respects the character of existing areas

- To consider adaptability and

diversity by creating places that can adapt and evolve easily over time

and that are characterized by variety and choice.

- To

understand and respect natural processes and features in development

design

- To maximize

energy-efficiency and promote sustainable design to reduce the resource

consumption, energy use, and carbon footprint of the built environment.

Figure

1: New development in an existing area combines both new and traditional

materials in innovative ways.

Urban

Design and Compatibility (Section 2.5.1 of the Official Plan)

“Community design generally deals with

patterns and locations of land use, relative densities, street networks, and

the allocation of community services and facilities. Urban design is more

concerned with the details relating to how buildings, landscapes and adjacent

public spaces look and function together. As the City grows and changes over

time, design of these elements should work together to complement or enhance

the unique aspects of a community’s history, landscape and its culture.

Encouraging good urban design and quality and

innovative architecture can also stimulate the creation of lively community

places with distinctive character that will attract people and investment to

the City. The components of our communities where urban design plays a key role

include:

§ Built form, including

buildings, structures, bridges, signs, fences, fountains, statues and anything

else that has been constructed, added or created on a piece of land;

§ Open spaces, including streets,

parks, plazas, courtyards, front yards, woodlots, natural areas and any other

natural or green open areas that relate to the structure of the city;

§ Infrastructure, including,

sidewalks, bike paths, transit corridors, hydro lines, streetlights, parking

lots or any other above- or below-grade infrastructure that impacts upon the

design of the public realm.

“Introducing new development in existing

areas that have developed over a long period of time requires a sensitive

approach and a respect for a communities established characteristics.”

“In general terms, compatible development

means development that, although it is not necessarily the same as or similar

to existing buildings in the vicinity, nonetheless enhances an established

community and coexists with existing development without causing undue adverse

impact on surrounding properties. It ‘fits well’ within its physical context

and ‘works well’ among those functions that surround it. Generally speaking,

the more a new development can incorporate the common characteristics of its

setting in its design, the more compatible it will be. Nevertheless, a

development can be designed to fit and work well in a certain existing context

without being ‘the same as’ the existing development”.

Urban

Design and Compatibility (Section 4.11 of the Official Plan)

“At the scale of neighbourhoods or individual

properties, issues such as noise, spillover of light, accommodation of parking

and access, shadowing, and micro-climatic conditions are prominent

considerations when assessing the relationships between new and existing

development. Often, to arrive at compatibility of scale and use will demand a

careful design response, one that appropriately addresses the impact generated

by infill or intensification.

Objective criteria that can be used to

evaluate compatibility include: height, bulk or mass, scale relationship, and

building/lot relationships, such as the distance or setback from the street,

and the distance between buildings. An assessment of the compatibility of new

development will involve not only consideration of built form, but also of

operational characteristics, such as traffic, access, and parking”.

1.3

Infill and Intensification

Infill

is development that occurs on a single

lot, or a consolidated number of small lots, on sites that are vacant,

undeveloped or where demolition occurs.

Infill may also refer to the creation of the lot or lots.

Infill

development at higher densities, in relation to existing neighbours, requires

good design to mitigate the potential impact of intensified building forms.

Residential intensification means intensification of

a property, building or area that results in a net increase in residential

units or accommodation and includes:

§ Redevelopment (the creation of new units, uses or lots on previously

developed land in existing communities), including the redevelopment of

Brownfield sites;

§ The development of vacant or underutilised lots within previously

developed areas;

§ Infill development;

§ The conversion or expansion of existing industrial, commercial, and institutional

buildings for residential use; and

§ The conversion or expansion of existing residential buildings to create

new residential units or accommodation, including secondary dwelling units and

rooming houses.

The

benefits of intensification (from CMHC’S ‘Healthy Housing 2005’) are:

§ More efficient use of

existing infrastructure and community facilities

§ Reduced expense on

entirely new infrastructure and transit systems

§ Lower energy

requirements for transportation due to reduced automobile travel and more

opportunities for public transport, walking and cycling

§ Reduced commuting

time and stress on the environment

§ More compact

development patterns protect greenspaces

§ Reduced rate of

encroachment on undeveloped areas

§ Reduced water

collection costs in clustered and more dense development

§ Lower water treatment

costs with larger treatment plants serving more homes

§ Mixed dwelling types

encourage people to stay in the same community as their housing needs change

1.4 When are Design Guidelines applied?

Design

guidelines are a tool to help achieve the Official Plan’s goals in the areas of

design and compatibility; they help implement Official Plan policies with

respect to the review of development applications for infill development.

This design guideline document will be applied to

all infill development affected by the Official Plan’s ‘General Urban’

designation including the following residential types: single detached,

semi-detached, duplex, triples, townhouses and low-rise apartments.

Please

also refer to Section 8.0 of this document, which explains the legislative

context under which the guidelines can be applied.

The design guidelines

that follow illustrate some of the important principles for design in the

public realm.

The

photographs and sketches are intended to illustrate only a few of the multitude

of solutions for successful infill development. Note that not all components of

every photograph illustrate successful solutions. As new projects are constructed, some

photographs may be replaced from time to time with photographs which better

illustrate the guidelines in this document.

The

City’s Design Guidelines are available at:

2.0

Streetscapes

The

public realm is made up of the public streets, sidewalks, boulevards, back

lanes, street furniture, public

utilities parks and open spaces. Civic life takes place in these outdoor

spaces that make up the public realm. In addition, private front yards form the

edge of the public realm. Both landowner

and pedestrian benefit when the front yards of buildings serve as landscaped

edges to the public sidewalk.

New

development should contribute to the character and legibility of public spaces,

and new streets should form natural, logical extensions of the existing city

street network. Cities are for people, and when the environment is designed

with a respect for pedestrians and cyclists, the quality of the public realm

improves.

For

healthy cities development must make public streetscapes attractive to

pedestrians, with trees and planting a priority. Sustainable cities have

beautiful large-canopied trees lining their sidewalks, providing natural

cooling and shade in the summer.

Where

neighbourhoods have diverse building forms and a less-than-successful urban

environment, infill buildings can fulfill the role of creating newer and more

desirable standards which can enhance the streetscape.

Design Guidelines

2.1

Contribute to an inviting, safe, and

accessible streetscape by emphasizing the ground floor and street façade of

infill buildings. Locate principal

entries, windows, porches and key internal uses at street level.

Figure

2: Buildings, with active facades close to the sidewalk, frame the street

to establish a human scale and connection to the public realm.

2.2

Reflect the desirable aspects of the

established streetscape character. If

the streetscape character and pattern is less desirable, with asphalt parking

lots and few trees lining the street, build infill which contributes to a more

desirable pedestrian character and landscape pattern.

Figure

3: The infill building on the left

reflects the style, mass and character of the existing building on the

right. A soft landscape edge has

been retained and new trees, which will contribute to the streetscape, have

been planted.

Figure

4: A sidewalk lined with trees is a pleasant pedestrian environment

Figure

5: A row of street trees creates an attractive street edge.

2.3 Expand the network of public sidewalks,

pathways and crosswalks, to enhance pedestrian safety.

2.4 Provide pedestrian-scale lighting that

points downward in order to minimize light pollution and prevent spillage onto

neighbouring properties. (Refer to the City’s Standard Site Plan Agreement,

Schedule ‘C’ - City Standards and Specifications, under Condition 19 - Exterior

Lighting)

2.5 Preserve

and enhance any existing decorative paving on streets and sidewalks.

2.6 Design universally accessible walkways,

from private entrances to public sidewalks.

2.7 Ensure that new streets, if private,

look, feel, function and provide similar amenities as do public streets,

including sidewalks and street trees.

3.0

Landscape

Design

guidelines

3.1 Landscape

the front yard and right-of-way to blend with the landscape pattern and

materials of the surrounding homes. Where surrounding

yards are predominantly soft surface, reflect this character.

Figure

6: The newly planted front yard of this infill home reflects the green

front yards of the surrounding homes.

3.2

Where the soft surface boulevard in the

right-of-way is limited, increase front yard setbacks to allow more room for

tree planting.

3.3

Design buildings and parking solutions to

retain established trees located in the right-of-way, on adjacent properties,

and on the infill site. To ensure

survival, trenching for services and foundations must take into account the

extent of the tree’s critical root zone. Replace trees with new ones if removal is

justifiable.

Figures

7 and 8: These images show how trees can be retained when driveways and

building footprints are sited carefully.

3.4

Provide street trees in continuous planting

pits or in clusters to support healthy growth.

Where the available soil volume and planting area is limited (less that

9m2 per tree), use materials and planting techniques (e.g. permeable

paving, Silva Cells or similar planting systems) that improve tree growth

conditions and limit the impacts of soil compaction and road salt.

3.5

Plant trees, shrubs, and ground cover

adjacent to the public street and sidewalk for an attractive sidewalk

edge. Select hardy, salt-tolerant native

plant material that can thrive in challenging urban conditions. (General

information on native species can be found on the Ottawa Forest and Greenspace

Advisory Committee’s web pages http://www.ofnc.ca/ofgac/)

Figure

9: Planted edges, on public or private land, enhance the public sidewalk

and streetscape.

3.6

For energy conservation, plant deciduous trees to shade south and south-west windows from the summer sun.

3.7

Support sustainability and improve

environmental performance by creating landscaped green roofs that are

functional and have aesthetic value.

3.8

In order to enhance a sense of separation

when infill is close to the street, use planting and/or low fencing to define

the boundary between the public space of the street and the semi-public space

of the front yard.

4.0 Building Design (Built Form)

Infill

development by its nature is contemporary construction within an historic

context, a stylistic blending of new with existing. The existing context, character and pattern

of an established neighbourhood can be recognized, while at the same time,

allow for the evolution of architectural style and innovation in built form.

Infill development should be a desirable addition to an existing neighbourhood.

This does not mean imitating historical styles and fashions of another era, or

conversely creating a total contrast in fabric or materials, but rather

recognizing the established scale and pattern of the context and the grain of

the neighbourhood.

The

goal of good infill development can be met within any architectural style.

Residential

infill should meet current building requirements and incorporate new

technologies. Various architectural styles can be very compatible with existing

structures and spaces. Through the use of quality materials and innovative

design, contemporary architectural styles can revitalize a street. Built form

rich in detail enhances public streets and spaces.

Design

Guidelines

4.1

Siting

4.1.1 Ensure new infill faces and animates the

public streets. Ground floors with

principal entries, windows, porches and key internal uses at street level and

facing onto the street, contribute to the animation, safety and security of the

street.

4.1.2 Locate and build infill in a manner that

reflects the existing or desirable planned neighbourhood pattern of development

in terms of building height, elevation and the location of primary entrances, the

elevation of the first floor, yard encroachments such as porches and stair

projections, as well as front, rear, and side yard setbacks.

Figure 10:

This urban infill matches the setbacks of surrounding homes and

preserves an established tree. The

front door faces the street, the ground floor elevation matches that of the

neighbours and the large first floor window contributes to an animated and

safe street.

Figure

11: This suburban infill respects

the scale, setback and materials of surrounding homes. The home takes advantage of a corner lot

by locating the garage and driveway on the side façade.

4.1.3 In determining infill lot sizes, recognize local lot sizes including lot

width, as well as the existing relationship between lot size, yard setbacks and

the scale of homes; recognize also the provisions of the Zoning By-law and the

Official Plan’s intensification policies.

4.1.4 Orient buildings so that their amenity

spaces do not require sound attenuation walls and that noise impacts are minimized. Design amenity areas such as second floor

balconies and roof top decks to respect the privacy of the surrounding homes.

4.1.5 In cases where there is a uniform setback

along a street, match this setback in order to fit into the neighbourhood

pattern and create a continuous, legible edge to the public street. In cases

where there is no uniform setback, locate the infill building at roughly the

same distance from the property line as the buildings along the abutting lots.

4.1.6 Contribute to the amenity, safety and

enjoyment of open spaces by offering living spaces that face them.

Figure

12: Living spaces facing onto public pathways support the quality of an

open space.

4.1.7 Avoid the arrangement of units where the

front of one dwelling faces the back of another, unless the units in the back

row have façades rich in detail, recessed garages and extensive

landscaping.

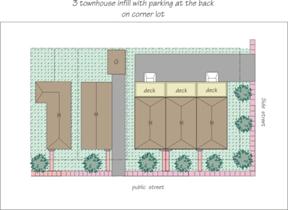

Figures

13 and 14: These two rows of infill townhomes, built around an internal

parking court, use extensive landscaping to enhance the development. Generous balconies predominate over

recessed garages.

Figure

15: The back row units, in the same development shown in Figures 13 and 14,

offer attractive landscaping, enhanced front entrances, large balconies and

recessed garages.

4.1.8 Determine appropriate side and rear

separation distances between existing homes and new infill homes/ infill

housing blocks to ensure appropriate light, view, and privacy. Consider how building height, site

orientation and the location of windows affect views, access to direct sunlight

and privacy.

Figure

16: An adequate separation distance between infill blocks, on this rear

private lane, ensures sufficient light, view and privacy for

residents. Richly detailed rear balconies and arbours define outdoor amenity areas,

while complementary screening and planting increase privacy.

4.1.9 Maintain rear yard amenity space that is

generally consistent with the pattern of the neighbouring homes. Do not break an existing neighbourhood

pattern of green rear yards by reducing rear yard setbacks.

4.1.10 Permit varied front yard setbacks if this

preserves and integrates existing natural features, such as mature trees or

rock outcroppings, or if this is consistent with the cultural landscape of the

neighbourhood. Note: some neighbourhoods enjoy consistent setbacks, others are

characterized by irregular setbacks.

4.1.11

Respect the grades and characteristic first

floor heights of the neighbourhood by not artificially raising or lowering

grades.

4.1.12

Position infill to take advantage of solar

heat and reflected light. Create a

layout where internal and external spaces benefit from solar orientation.

4.2

Mass/Height

4.2.1 Design infill in a manner that contributes

to the quality of the streetscape, and that considers the impacts of scale and

mass on the adjacent surrounding homes.

Figure

17: The height, width, materials and

landscape treatment of this infill echo the existing units on either side.

4.2.2 In cases where new buildings back on to

lower-scale residential properties or public open space, set the building(s) so

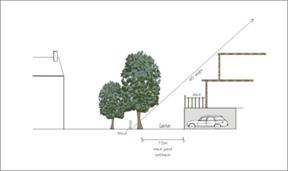

that it does not project into a 45 degree angular plane from the rear property line, in order to reduce

the impact of the potential loss of sunlight or privacy on neighbouring

properties. (A 45 degree angular plane is measured from a rear lot line and projects at a 45

degree angle toward the development.) For larger infill development, design

within an appropriate angular plane, and provide a suitable buffer zone in

order to protect a neighbour’s access to adequate light, view and privacy.

Figure

18: Building within angular planes protects existing neighbour’s privacy

and access to sunlight.

4.2.3 Where the new development is higher than

the existing buildings, create a transition in building heights through the

harmonization and manipulation of mass. Add architectural features such as

porches and bays, and use materials, colours and textures, to visually reduce

the height and mass of the new building.

4.2.4 Locate roof projections, which provide

access to decks and patios, so that height impacts are reduced.

4.2.5 To reduce the perceived height of the

building, as contributed to by the parapet around a roof top use, consider

materials such as frosted plexiglass which reduce height impacts and at the

same time maintain a level of privacy.

4.2.6 If the new development is significantly

larger than the existing adjacent buildings,