EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Under the Ottawa 20/20

initiative, “A Green and Environmentally-Sensitive City” was identified as one

of seven principles that will be used to guide the City when making day-to-day

decisions. As the City’s population is

projected to grow 50% over the next 20 years, the growth will need to be

managed in a sustainable way, one that reinforces the importance of the natural

areas that are so highly valued by City residents.

Ottawa seeks to

preserve its natural diversity by planning on the basis of natural systems

whereby natural processes and ecological functions are protected and

enhanced. This principle was

incorporated into the 2003 Ottawa Official Plan and a number of environmental

strategic directions were developed to meet this objective. The Greenspace Master Plan was identified as

one of these strategic initiatives that would identify all of the greenspace

opportunities in the City and provide a means to secure them. Within this context, the Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study (UNAEES) was mandated to identify woodlands,

wetlands and ravines throughout the urban area that are worthy of

protection. The purpose of the study

was to identify and to assess the relative environmental value of these natural

areas across the entire urban area, and make recommendations for management of

these lands aimed at their long-term sustainability.

The consultant team of

Muncaster Environmental Planning Inc. and Daniel Brunton Consulting Services

with Nancy Smith, Planner and Mediator, were commissioned in December of 2002

to undertake the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study

(UNAEES). The key objectives of the

Study are to:

1. Establish a relative environmental evaluation

of remnant natural areas within the urban boundary of the City of Ottawa; and

2. Propose

ecological, recreational and stewardship management recommendations for

individual natural areas aimed at their long-term sustainability, including how

passive (low-impact) recreational uses may be better programmed to sustain and

enhance natural features on site.

As the next

phase of the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study, City staff

will be developing an implementation strategy for urban natural features as

part of the Greenspace Master Plan.

Background

The Urban Natural

Areas Environmental Evaluation Study provides a consistent science based

approach to determine the relative environmental value of remnant areas of

woodlands, wetlands and ravine lands within the urban area of the City. The study area for Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study is defined by the urban boundary as depicted on

Schedule B of the 2003 Ottawa Official Plan.

The assessment of the environmental condition and the impacts on natural

lands within the urban context is uniquely different to conditions and impacts

that occur in the less developed rural context. The natural features contained within Villages and rural areas

were therefore excluded from this exercise.

Natural areas within Villages and rural areas will be assessed through

other planning initiatives such as subwatershed studies and Community Design

Plans or have already been addressed by the former Region’s Natural

Environmental System Strategy Study (NESS).

Approximately 2,660

hectares of natural areas fall within the definition of woodlands, wetlands and

creek/ravine lands within the urban boundary of the amalgamated City of

Ottawa. These lands are an important

element of the urban landscape. They

contribute significantly to public health, community enjoyment, property

values, and many areas sustain regionally and even provincially important

natural features and values.

The Urban Natural

Areas Environmental Evaluation Study developed a comprehensive process for

defining and assessing the environmental values and attributes of urban natural

areas. The main steps are:

- Identification

of candidate sites;

- Assessment and

description of each candidate site;

·

Evaluation of sites applying environmental criteria to determine high, moderate

or low ecological value; and,

·

Development of management recommendations (ecological and recreational)

for each natural area.

A summary of key study steps and findings is provided below.

Identification of candidate Urban

Natural Areas

Natural features such

as woodlands, wetlands, ravine systems and creek corridors were all identified

for consideration under the study.

Neither land ownership, zoning nor development status were factors in

determining candidate urban natural areas.

If the candidate natural area physically existed in the spring of 2003,

it was considered eligible for inclusion in the study unless a building permit

had been issued for the site. A minimum

size requirement of 0.8 hectares was used to establish the list of candidate sites

for evaluation. An initial list of 180

candidate urban natural areas was presented at the first set of public open

houses held in the spring of 2003.

Refinements to the

candidate site list were made based on input received from the public, various

environmental groups, the project Steering Committee and the Public Advisory

Committee. These refinements included

additional sites, expansion of identified sites, merging and splitting of

sites, and deleting sites due to major site alterations. A final list of 187 urban natural areas was

compiled which includes new areas previously unevaluated and areas that have

already been designated Urban Natural Features in the City’s Official

Plan.

Evaluation Framework

An evaluation framework

was developed for the study that provides a comparative environmental

evaluation consistent for all sites.

Nine evaluation criteria were selected to rate the ecological value of

urban natural areas:

·

Connectivity

·

Absence of Disturbance

·

Habitat Maturity

·

Natural Communities

·

Regeneration

·

Representative Flora

·

Significant Flora and Fauna

·

Size and Shape

·

Wildlife Habitat

The evaluation

framework provides a clear definition of each criterion that is then further

broken down into five threshold levels.

Each threshold is assigned a rating of one through five, with a rating

of 5 being the most ecologically valued or least disturbed. The rating assigned to each of the nine

individual criteria was then combined to give an overall rating for the natural

area. This overall rating was used to

generally group the natural areas into three levels:

- Low Ecological Rating – an overall rating

of less than two,

- Moderate Ecological Rating - an overall

rating from two to less than three;

- High Ecological Rating - an overall

rating of three or greater.

The evaluation

framework (evaluation criteria and scoring system) was developed in

consultation with the Steering Committee, Public Advisory Committee and the

general public.

Fieldwork Component

Once the candidate

natural area sites were selected and the evaluation criteria developed, the

fieldwork component commenced in June of 2003. The objective of the fieldwork

program was to ensure that sufficient ecological information was gathered to

provide a relative environmental evaluation of each site within the system of

Ottawa’s urban natural areas. For many

sites, especially within the former City of Ottawa, an extensive amount of

information was already available through past studies such as the Natural and

Open Spaces Study. For these sites the

validity of the existing information was verified with a field review of the

site in 2003. The data was updated with

a description of the current state of ecological disturbance, notes of any significant

changes in the features and functions of the natural area since the last

evaluation, and the boundary of each natural area was refined.

For sites where less

ecological information existed, a more detailed field survey was

undertaken. This more detailed site

assessment included an examination of representative portions of the different

vegetation communities and landforms of the natural area to identify the

ecological functions of the site. The

field investigations collected information on forest stand ages, natural area

size, number and rarity of community types, flora and fauna species,

disturbance levels, ecological functions, geological landforms, other unique

attributes, linkages to other natural areas, wildlife habitat, wildlife usage and

corridors and existing recreational uses.

Site disturbances such as non-native species, trail use, dumping and

vandalism were recorded.

Recreational Component

The terms of reference for the study also

required the consultants to evaluate the passive recreational value of the

site. This was accomplished by an assessment of the capacity of the site to

accommodate human uses such as recreation activities, with the focus on

assessing existing and potential threats to environmental features and

functions by various levels of human activity.

Evidence of existing unstructured

recreational activity, such as trails, was documented along with an indication

of how formal the activity appears. The

level of detail for the recreational component is not extensive, for example

recommendations for specific trail routes is not defined, although portions of

the natural areas to avoid are described.

Identification of stewardship

opportunities is another part of the recreational component included in the

description of natural areas.

The primary objective of the

recreational component is to protect the important natural features and

functions of the natural areas by taking a look at whether sites could also support

low impact recreation and which would be likely to benefit from stewardship

opportunities. This component did not

aim to be a recreational planning exercise, but will add information to each

site to help the recreational planners and operations staff in managing

existing and future recreational activities without compromising the integrity

of the natural features.

Evaluation of Candidate Urban Natural Areas

A total of 114 sites

of the 187 sites were assessed through the review of existing information and

field visits. These sites were carried

forward for evaluation. The nine

evaluation criteria were applied to each of these sites resulting in an overall

environmental rating of low, moderate or high being assigned to each area. A further review of the individual

evaluations was undertaken to confirm that the overall rating assigned to each

natural area was appropriate. One

hundred and fourteen (114) urban natural areas are considered complete and have

been evaluated and rated using the evaluation framework described in Section

3.1.

A total of

seventy-three (73) sites were not evaluated either because access to the sites

was not granted by the landowner (no response or refusal) or due to time

limitations imposed by the field season requirements. A significant amount of existing ecological information is

available for twenty-four (24) of the remaining natural areas. These areas require only an ecological

condition check in order for the evaluation criteria to be applied, but access

to the site is required. The remaining

forty-nine (49) natural areas require a full field assessment prior to

proceeding with the evaluation component.

The boundaries of all

candidate urban natural areas have been digitized and are illustrated on a

citywide aerial photo mosaic map along with the overall environmental rating

(Figure 3). For those sites not

evaluated, the required level of field assessment: 1) Full ecological assessment; or, 2) Ecological condition check,

is indicated on the map.

Summary of Findings

The 187 natural areas

cover approximately 2,660 hectares of the City’s urban area, or 7.7 percent of

total land surface area within the urban boundary (not including significant

water bodies). A total of 114 sites representing

about 1,497 hectares have been evaluated representing four percent of the urban

area. For discussion purposes, the City

has been divided into four geographical sub-areas: West, Central, South and East.

A summary of the overall ratings for the evaluated natural areas is

provided in the following table:

|

Table

2. Summary of Overall Natural Area

Ratings by Urban Sub-Area.

Percent

is the percent of sites evaluated to date

|

|

Sub-Area within City of Ottawa’s Urban Area

|

Sites High Overall

|

Sites Moderate Overall

|

Sites Low Overall

|

Total Sites Evaluated to Date

|

Sites to be Evaluated

|

|

No.

|

Percent

|

No.

|

Percent

|

No.

|

Percent

|

|

West

|

6

|

26

|

10

|

44

|

7

|

30

|

23

|

12

|

|

Central

|

16

|

22

|

24

|

33

|

32

|

45

|

72

|

24

|

|

South

|

3

|

38

|

3

|

38

|

2

|

25

|

8

|

24

|

|

East

|

4

|

36

|

4

|

36

|

3

|

28

|

11

|

13

|

|

Totals

|

29

|

25

|

41

|

36

|

44

|

39

|

114

|

73

|

The forty-four sites

rating the lowest represent 39 percent of the sites with a completed

evaluation, while the twenty-nine high rated sites represent 25 percent of the

sites evaluated. The twenty-nine

natural areas rating high cover 860 hectares, with the moderate and low sites

representing 450 and 129 hectares, respectively.

Site specific

ecological, recreation and stewardship management recommendations will be

provided for each candidate urban natural area. The management recommendations include operational measures with

an emphasis on mitigating observed disturbances or other existing negative

impacts. Measures for rehabilitating or

enhancing the ecological features and functions of the natural areas are also

provided, including control of non-native plant populations, removal of garden

waste and debris, trail alignments, naturalization, and placement of

interpretative signs.

New and significant

ecological features were found in many urban natural areas of the City of

Ottawa. The features included plants of

interest at a local, regional and provincial level. Relatively undocumented natural areas with significant natural

assets were found, such as Forestglen Park in the east and Hazeldean Woods Park

in the west. Both of these sites have

been rated high overall and, until this study, had been very poorly documented,

or not at all. Other sites such as

Heart's Desire Forest, Mud Lake and Trillium Woods that received high overall

ratings were well documented by existing studies and are well known by the

community.

Strong healthy

functioning ecosystems continue to exist despite relatively small size and

intense urban pressure in most areas.

However, the ecological functions of many natural areas are being

impaired by human activities and disturbances.

The adoption and implementation of the management recommendations for

natural areas are critical to sustaining a healthy natural system within the

urban area.

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Scope and Study

Objectives...................................................................................... 1

1.2 Report Structure........................................................................................................ 3

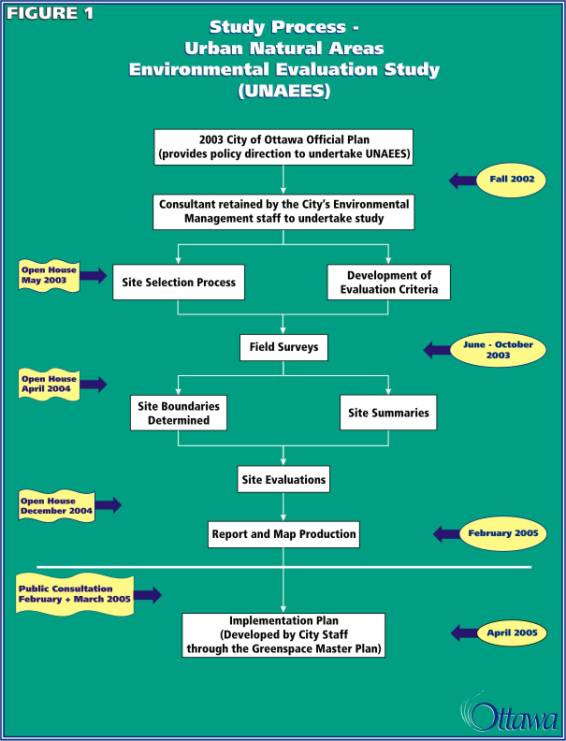

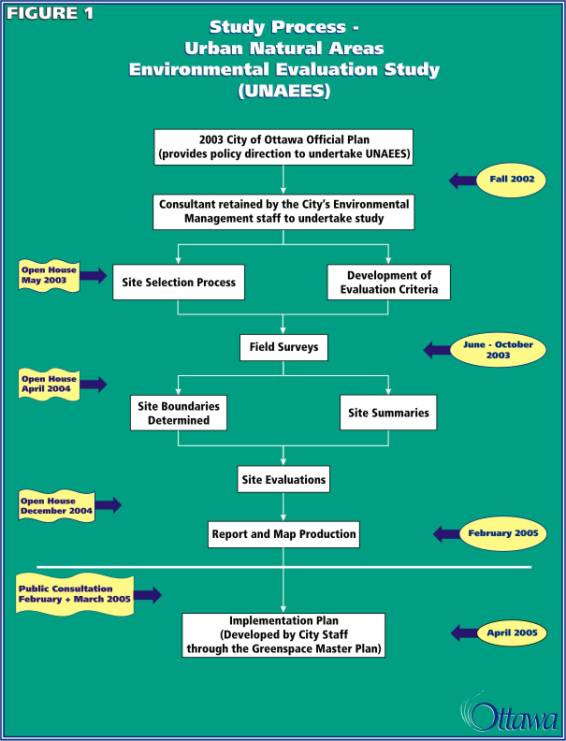

1.3 Study Process........................................................................................................... 4

2.0

SITE SELECTION............................................................................................................... 7

2.1 Review of Similar

Studies........................................................................................... 7

2.2 Approach to Site

Selection........................................................................................ 8

2.3 Identification of

Candidate Sites................................................................................. 9

2.4 Candidate Site

Results............................................................................................. 11

3.0 METHODOLOGY............................................................................................................. 12

3.1 Development of

Evaluation Framework.................................................................... 12

3.2 Landowner Permission............................................................................................. 24

3.3 Fieldwork

Program.................................................................................................. 25

3.4 Data Collection and

Field Surveys............................................................................ 25

3.5 Recreational Component.......................................................................................... 29

3.6 Database Production............................................................................................... 30

4.0 EVALUATION RESULTS................................................................................................. 31

4.1 Urban Natural Area

Boundaries and Mapping.......................................................... 31

4.2 Site Ratings............................................................................................................. 32

4.3 Management Recommendations............................................................................... 36

4.3.1 Ecological Management Measures............................................................... 37

4.3.2

Recreational Management Measures ........................................................... 40

4.3.3

Stewardship Opportunities........................................................................... 42

5.0 ANALYSIS of SITE

RESULTS......................................................................................... 44

5.1 Interesting Findings

and City-wide Trends................................................................ 44

5.2 West Sub-Area....................................................................................................... 45

5.3 South Sub-Area...................................................................................................... 46

5.4 Central Sub-Area.................................................................................................... 47

5.5 East Sub-Area......................................................................................................... 48

6.0 DATA STORAGE and

MAPPING..................................................................................... 49

7.0 NEXT STEPS .................................................................................................................... 50

8.0 REFERENCES................................................................................................................... 52

FIGURES

Figure 1 Study

Process........................................................................................................... 6

Figure 2 Site

Selection Methodology..................................................................................... 10

Figure 3 Site Evaluation Results Map .............................................................................. at

rear

TABLES

1 Comparison of Municipal Natural Area Studies...................................................................... 8

2 UNAEES Field Site

Sheet................................................................................................... 28

3 Summary of Overall

Natural Area Ratings by Urban Sub-Area............................................. 34

ANNEX

Annex A Individual

Site Summary Reports and Mapping (CD)

APPENDICES (under separate cover)

APPENDIX A - Vascular

Plants of the City of Ottawa, Ontario, with Identification of

Significant

Species by D. F. Brunton

APPENDIX B Public Consultation Details by Nancy Smith Planning

and Mediation

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the constant and valuable support

of the Environmental Management Staff of the City of Ottawa, with special

thanks to Barbara Gray, Susan Murphy, Deborah Irwin and Cynthia Levesque. The Mapping and Surveys Unit of the City,

in particular Michael Willison and Stephen Perkins, was outstanding in

developing maps for the open houses and producing the final individual site

maps.

The Steering Committee and Public Advisory Committee should also be

acknowledged for their dedicated participation throughout the study

process. Committee members provided

valuable advice at key milestone stages of this project.

Nancy Smith of Nancy Smith Planning and Mediation looked after the

communication component of the project, including organization of the open

houses, chairing the Steering and Public Advisory Committee Meetings, and

production of the backgrounder mail outs and Appendix B – Public Consultation

Details. Nancy also led the way on the

recreational component of the natural area summaries and was a much-appreciated

influence through the entire study.

Isosceles Information Solutions Inc. of Manotick generated the

initial site maps and digitized the site boundaries.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Scope and Study Objectives

Over the next

20 years the City of Ottawa’s population is projected to grow by up to 50

percent, surpassing the one million mark (City of Ottawa, 2003). Although this level of growth will open many

new opportunities for residents, the growth will need to be managed in a

sustainable way, one that reinforces the importance of the natural feature

areas that are so highly valued by City residents.

Under the Ottawa

20/20 initiative, “A Green and Environmentally-Sensitive City” was identified

as one of seven principles that will be used to guide the City when making

day-to-day decisions. Ottawa seeks to

preserve its natural diversity by planning on the basis of natural systems, to

protect and enhance natural processes and ecological functions. This principle was incorporated into the

2003 Ottawa Official Plan (City of Ottawa, 2003) and a number of environmental

strategic directions were developed to meet this objective. One of the major deliverables is the

Greenspace Master Plan (Policy 2.5.4).

This plan is to identify and characterize all of the greenspaces in the

City, evaluate greenspaces in terms of their value in the city, and develop a

Greenspace Network. A key component of

the Greenspace Master Plan is the identification and evaluation of urban

natural features. As stated in Section

3.2.3, Urban Natural Features, of the 2003 Ottawa Official Plan, a comprehensive study that identifies all

significant natural features and functions and assesses their relative

environmental value across the entire urban area is required in order to

establish environmental protection priorities for the City. The Urban Natural Areas Environmental

Evaluation Study (UNAEES) was commissioned in 2002 to fulfill this OP direction

and provide an important contribution to the Greenspace Master Plan.

The Urban

Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study (UNAEES) provides a relative

environmental evaluation of the remnant urban natural areas in the City. Although functioning at a different scale to

rural natural areas, urban areas provide natural environmental benefits as well

as recreational and educational opportunities at a local, community level. The natural features contained within

Villages and rural areas are studied at a detailed level through mechanisms

such as subwatershed studies and community design plans building upon the

Natural Environment System Strategy (NESS) database. The study area for UNAEES is defined by the urban boundary as

depicted on Schedule B of the 2003 Ottawa Official Plan. Municipal amalgamation provides an

opportunity for a Citywide approach to a comprehensive, relative,

science-based, environmental evaluation for the over 180 identified remnant

urban natural areas.

The Urban

Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study identifies features such as woodlands,

wetlands, vegetated ravine systems and creek corridors throughout the City’s

urban area. The Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study evaluates the urban natural areas in both public

and private ownership in the urban and urbanizing areas of the former

municipalities of Ottawa, Nepean, Kanata, Goulbourn, Rockcliffe, Vanier,

Cumberland and Gloucester.

There are

approximately 2,660 hectares of natural area within the urban area of the

amalgamated City of Ottawa. Urban

natural areas are an important element of the urban landscape. They contribute significantly to public

health, community enjoyment, property values, and many areas sustain regionally

and even provincially important natural features and values.

The Urban

Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study includes an extensive process for

defining and assessing the environmental value of urban natural areas. The main study steps are:

- Identification and

selection of candidate urban natural areas;

- Assessment and

description of each candidate site based on field investigations;

- Evaluation of the site

applying the evaluation criteria to assign a high, moderate or low

ecological value; and,

- Development of management

recommendations (ecological, stewardship and recreational) for each evaluated

site.

The result

is an integrated framework and consistent level of analysis for urban natural

areas within the whole amalgamated City of Ottawa to assist in the development

of a uniform policy direction. The

Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study provides a toolbox of

technical information. City staff can draw from these tools to prepare a

comprehensive urban natural areas strategy.

The information will also be useful in the preparation of area planning

studies, community design studies, environmental management plans and watershed

and sub-watershed planning studies. In

addition, the information obtained through this Study will assist in the

preparation of Environmental Impact Statements for urban natural areas.

In developing

a strategy for the protection of natural areas, other factors such as past and

emerging development decisions, links to other greenspaces, accessibility,

equitable distribution, recreational attributes and aesthetics will need to be

considered. However, this analysis is

beyond the scope of this Study. Through

the development of the Greenspace Master Plan, an implementation strategy will

be prepared by City staff which will determine the protection recommendations

and securement tools applicable for each natural area. The identification of management

recommendations and recreational opportunities for each area, through UNAEES,

will provide further insight into the assessment of these factors. The information in this Study will also

contribute to the public’s understanding of the value and role of natural areas

in the City.

In summary, the key objectives of

the UNAEES are to:

- Establish a relative

environmental evaluation of remnant natural areas within the urban

boundary of the City of Ottawa; and

- Propose management

recommendations for individual natural areas aimed at their long-term

sustainability, including how passive (low-impact) recreational uses may

be better programmed to sustain and enhance natural features on site.

The public has had an important role in the Study by providing valuable

knowledge of the natural area sites, including their characteristics, value and

use. The UNAEES has given the public

the opportunity to learn more about their urban natural areas, and to have

input into the site selection process and development of the evaluation

framework through two sets of open houses and distribution of study

bulletins. A third open house was held

in order for the public to review the results of the overall environmental

rating assigned to each evaluated area and to learn more about the next steps

involved in implementing the study findings.

For details on the public consultation program, please consult Appendix

B.

The Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study

consists of this report with two separate appendices that are described below.

Urban Natural Areas Environmental

Evaluation Study Final Report

This report describes the scope and objectives of the study and the

overall methodology developed to identify, evaluate and assess natural areas

within the urban portion of the City of Ottawa based on their environmental

features and functions. The methodology

includes the site selection process, landowner notification, the evaluation

criteria and framework, field assessments, and evaluation of the urban natural

areas. The second portion of the report

describes the results of the evaluation process, including ratings of the urban

natural areas and ecological, recreational and stewardship management

recommendations, and highlights trends and interesting findings of the field

inventories.

Annex A of this report provides on CD the

site summary reports and ratings for each of the 114 evaluated sites. For each evaluated site, the following

information is provided:

1) Site Description including details on size, ownership, the

ecological features and functions of the natural area, including connectivity,

interior habitat, disturbance and condition, adjacent land use, invasive

plants, vegetation communities and habitats, representative flora and fauna and

significant features and species.

2) Environmental Rating Matrix identifying the overall rating

attributed to the urban natural area, along with ratings for each of the nine

evaluation criteria.

3) List of Native Flora and Fauna.

4) Site Boundary Mapping at a scale of 1:3,000, on a 2002 colour aerial

photography base, of the urban natural area.

5) Management Recommendations, including passive (low impact)

recreation opportunities.

6) Site References.

Appendix A - Vascular

Plants of the City of Ottawa, with Identification of Significant Species by

D.F. Brunton

A major deliverable from the Urban Natural

Areas Environmental Evaluation Study is an expansion and update to t “Significant Vascular Plants list”

published by the former Region of Ottawa-Carleton. This

Significant Vascular Plants listThis is the first

time all plants documented in Ottawa (rare, common, native, non-native) have

been compiled in one checklist.

Appendix B - Public

Consultation Details

Appendix B provides a record of the public consultation activities

held during the course of the study, including the establishment of a public

advisory committee, production of study bulletins and holding of public open

houses. At each step in the study,

there was a significant opportunity for the public to provide value input to

the process and methodology. Important

public comments were received and incorporated into the study as part of the

site selection, evaluation criteria and site boundary components in particular.

Minutes from the Public Advisory Committee meetings, e-mails and other

correspondence from individuals, summaries of comments at the public open

houses and dozens of completed comment sheets from the open houses are the

primary records for public comments.

1.3

Study Process

The development of the 2003 City of Ottawa

Official Plan identified the need for evaluation of urban natural areas among

the amalgamated areas of the expanded City.

A number of remnant natural areas both in private and public ownership are

found within the more urban and urbanizing centres for the former cities of

Nepean, Kanata, Goulbourn, Ottawa, Vanier, Rockcliffe, Cumberland and

Gloucester. These remnant areas have,

however, received inconsistent levels of evaluation and policy direction in the

former municipalities Official Plans.

Municipal amalgamation provided an opportunity for a Citywide approach

to a comprehensive, relative environmental values evaluation for remnant urban

natural areas.

The City’s Environmental Management Staff

developed the Terms of Reference for the Urban Natural Areas Environmental

Evaluation Study and completed the consultant selection process in late

2002. Staff then formed the Public

Advisory and Steering Committees to support the study. The Public Advisory Committee supplied community perspective, insights, and

information. It also provided an

initial line of communication to the larger community about the study. Members included representatives from the

City’s Environmental Advisory Committee, expert non-governmental organizations

such as the Ottawa Field-Naturalists and other environmental professionals, and

community groups with an interest in urban natural areas. Members of the Steering Committee included

representatives with expertise in natural environment from the City,

Conservation Authorities, National Capital Commission (NCC), City’s Ottawa

Forests and Greenspace Advisory Committee, and Ministry of Natural

Resources. Staff

and the project consultant worked together to finalize the work plan. A communications plan was then developed.

Public consultation

included the two sets of Open Houses in three different geographic locations in

the west, east and central area with a third open house

in the central location. The communications plan also used interactive

tools such as e-mail, the City web site, as well as distributing study

bulletins and public announcements in French and English newspapers.

Figure 1 illustrates

the study process undertaken for the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation

Study. Each step of the process is

described in the following sections of this report:

·

Section 2.0 - Site Selection Process

·

Section 3.0 - Methodology

·

Section 4.0 - Evaluation Results

·

Section 5.0 - Analysis of Site Results

·

Section 6.0 - Data Storage and Mapping

·

Section 7.0 - Next Steps

2.0 SITE SELECTION

2.1 Review of Similar Studies

Several studies of municipal natural areas

have been completed in Ontario and other parts of the Country. With an emphasis on the Ontario municipalities,

the review examined the methodology, findings and conclusions of these studies,

including studies of natural areas in Edmonton (Westworth, 2001), Halton Region

(Geomatics, 1993), Markham (Gore & Storrie, 1992), London (Bergsma, 1999), Waterloo (CCL, 1993), and York Region

(Gartner Lee, 1994). Table 1 compares

some of these other studies with the Natural and Open Spaces Study (NOSS)

completed in 1998 for the former City of Ottawa, the Natural Environment

Systems Strategy (NESS) of the former Region of Ottawa-Carleton (1997), and the

current Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study.

These studies from other municipalities were most useful in

establishing the evaluation criteria used in the Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study and the corresponding draft thresholds for the

ratings within each criterion.

Including all urban natural areas in Ottawa in

the study made the site selection process more straightforward than in some

other studies. Instead of rating the

sites at this initial stage, all sites with any notable natural feature or

function potential were carried forward for study. Some other municipal studies examined only the potentially most

significant of the total list of candidate urban natural areas (Westworth, 2001), or

examined only remnant natural areas that were not protected by existing

policies (CCL, 1993; Bergsma, 1999).

Other municipal studies examined both urban and rural areas (CCL,

1993; RMOC, 1997, Westworth, 2001) but rural natural areas were not included in

the mandate of the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study. Other studies did not examine the natural

areas in the level of detail completed in the Urban Natural Areas Environmental

Evaluation Study or completed analysis of far fewer sites. In contrast to the 187 urban natural areas

carried forward in this Study, CCL (1993) examined 21 woodlands in the City of

Waterloo and Westworth (2001) evaluated 66 sites in the City of Edmonton.

Looking at the earlier Ottawa NOSS, there are several important

differences. The Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study evaluates only natural features and functions

and restricts the recreational component to implications for maintenance and enhancement

of the natural environment. The NOSS,

however, examined several types of open spaces in addition to natural areas,

including parks, schools, open spaces and manicured green spaces. The NOSS also examined watercourses and

their aquatic habitat. An analysis of

the feasibility of retaining natural areas and open spaces was also conducted

as part of the main study.

Many studies incorporated policy applications and an implementation

strategy (City of Ottawa, 1998; Westworth, 2001). As discussed in Section 7 of this report, policy and implementation

of the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study will be completed as

part of the City of Ottawa’s Greenspace Master Plan.

|

Table 1. Comparison of Municipal Natural Area Studies

|

|

Theme

|

Natural and Open Spaces Study

|

Natural Environment Systems Strategy

|

Edmonton

|

Waterloo Woodlot Study

|

UNAEES

|

|

Municipal area covered

|

City of Ottawa

[former]

|

Region of

Ottawa-Carleton

[former]

|

City of Edmonton

|

City of Waterloo

|

City of Ottawa

[amalgamated]

|

|

Type of area covered

|

Urban

|

Urban and rural

|

Urban and rural

|

Urban and rural

|

Urban

|

|

Purpose of study

|

Facts and policy

|

Facts and policy

|

Facts and policy

|

Facts only

|

Facts only

|

|

Nature of data

|

Ecological and social

|

Ecological

|

Ecological

|

Ecological and social

|

Ecological

|

|

Level of analysis

|

Fine

|

Coarse

|

Fine

|

Fine

|

Fine

|

|

Type of evaluation

|

Comparative

|

Comparative

|

Comparative

|

Comparative

|

Comparative

|

2.2 Approach

to Site Selection

The study area is delineated by the

boundary of the Urban Area as identified Schedule B of the 2003 Ottawa Official

Plan (adopted 2003). Neither the

National Capital Greenbelt nor rural areas in the City of Ottawa were included

in this study. The natural system operating in the rural area of the City of

Ottawa have been studied at a detailed level through such means as Greenbelt

Master Planning, subwatershed studies and the Natural Environment System

Strategy (RMOC, 1997). As well, the Greenbelt and many of the rural portions of

the City include large and diverse natural areas such as Shirley’s Bay, Stony

Swamp, Marlborough Forest, Richmond Fen and Mer Bleue. These areas constitute significant natural

landscapes with more comprehensive systems of natural features and functions

than those in the urban area.

Comparisons among such a spectrum of rural and urban natural areas in a

single study would have been unbalanced.

Land ownership, zoning and development

status were not factors in determining candidate urban natural areas. If the candidate natural feature existed in

the spring of 2003, it was considered eligible for inclusion in the study unless a building permit removing the feature

had been issued for the site.

Terrestrial natural features such as woodlands,

ravine systems, and wetlands were all considered in the Study. Although watercourses themselves were not

explicitly studied, the vegetated portion(s) of the riparian corridors along

the watercourses were included as candidate areas. Lands that provide an important associated function for the core

natural area, such as adjacent early successional meadow habitat, were also

included for consideration within the candidate areas. For example, the Britannia Conservation

Area, Navan Road at Page Road, Conroy Swamp and Petrie Island also include

adjacent meadow habitat. The meadow

habitat would likely not be considered an urban natural area site on its own,

but is included as part of the urban natural area site because it adds to the

features and functions of the natural area.

A minimum size of 0.8 hectares was set for

candidate urban natural areas. This was

based on the methodology of other similar technical studies in Canadian

municipalities and the recognition that significant self-sustaining ecological

function is unlikely to occur in an area smaller than 0.8 hectares (Westworth,

2001). If a natural feature, such as a

specialized wetland habitat, of less than 0.8 hectares was noted, however, it

also was eligible for inclusion in the candidate site list. These smaller areas were considered on a

case-by-case basis.

2.3 Identification

of Candidate Sites

As an initial step, 1999 colour aerial photography was used to

identify candidate urban natural areas.

This was augmented by existing environmental inventory reports and

personal knowledge of the City’s natural areas. The existing information included natural environment inventories

and assessments completed as part of the Natural and Open Spaces Study, Natural Environment Systems Strategy, sub-watershed

studies, master drainage plans, environmental assessments and screenings, and

Official Plan reviews, as well as site specific environmental impact statements

and tree preservation plans. The 2003

Ottawa Official Plan was also reviewed to ensure that all lands designated Urban Natural Feature on Schedule B had

been included in the candidate site list.

Input on candidate areas was also received from the Steering and Public

Advisory Committees and the general public.

The candidate urban natural areas were roughly marked on the aerial

maps. A “windshield check” of the areas

in the spring of 2003 provided a field truthing for the initial screening. The “windshield check” provided confirmation

that the candidate urban natural area still existed. Some sites were deleted if major site alterations had recently

occurred which eliminated the potential natural environment feature and

functions on the site, or if the site clearly did not contain natural environment

attributes to merit consideration as a candidate urban natural area. As well, during the “windshield check” some

areas that were not picked up in the initial review of aerial maps were added

as candidate sites based on initial observations of potential ecological

features.

Because of this screening, none of the sites retained for further

study were completely lacking in natural features or value. Regardless of their final evaluation, all

sites studied were included on the list because of apparent natural value.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Windshield

Survey”

to confirm presence of

feature/function

|

|

|

|

|

2.4 Candidate

Site Results

An initial list of 180 candidate urban natural areas was presented at

the first set of public open houses held in the spring of 2003. For presentation purposes, the urban area

was divided into 4 geographical sub-areas; west, south, central and east. Aerial photography maps of each sub-area

illustrated the identified candidate urban natural areas with a crude polygon

boundary. These maps were also reviewed

by the project Steering Committee and Public Advisory Committee, and were

presented on request to several environmental groups.

From the comments received from the public, various environmental

groups, and the project Steering and Public Advisory Committees, eight new

sites were added to the list of candidate areas. Six sites suggested by the public were added as expansions of

natural areas already on the working list.

There was also some merging and splitting of sites, as recommended by

the public and the study team.

Sixteen sites recommended by the public were not considered to have

natural values, and were referred to the Greenspace Master Plan project

team. Each of these suggested sites was

considered with a field check and/or review of existing background

information. Small site size and poor

site conditions were two key factors in not carrying a site forward as a candidate

urban natural area.

A final list of 187 urban natural areas was compiled and is provided

on Figure 3 and in Annex A of this report.

3.0

METHODOLOGY

3.1 Development of Evaluation Framework

The evaluation criteria are the means for assessing

the comparative ecological features and functions among the urban natural

areas. The criteria provide the vehicle

for transforming the field observations of a natural area into a rating system. The site summaries describe the

characteristics of a site, for example, how old are the trees, how large is the

site, what are the disturbances. The

criteria take these observations and apply an evaluation framework to provide a

comparative rating for each natural area.

This approach allowed for a consistent, comparative, science-based

assessment of the urban natural areas of Ottawa in one field season.

We describe this evaluation framework as

indicators-based. Each of the nine

criteria is an indicator of an aspect of the natural area associated with

ecological value. The links between the

indicator and ecological value is described in the definition of each

criterion. For example, within the

definition of Connectivity (Criterion 1) is the following statement:

Linkages to other urban natural areas such

as woodlots, watercourse corridors and wetlands provide corridors for movement

and assist in maintaining the health of natural communities including diversity

and genetic health.

In other words, more connectivity provides

communities with greater diversity and genetic health, factors in a healthier

and more sustainable natural area.

For a second example, within the definition

of Absence of Disturbance (Criterion 2) is the following statement:

Physical disturbance within habitats

significantly reduces native biodiversity, the quality of ecological functions,

and ecological integrity within natural habitats. The physical condition of the area is a good indicator of overall

natural quality and significance.

The degree of disturbance, in other words,

is a good indicator of the natural quality of an area.

We also call this framework an

indicators-based approach because we are collecting observations of aspects of

the natural areas that go beyond description.

A description would say “The site is 4 ha in area.” An indicator says “This site has an

excellent size, because it is greater than 20 ha in area, and we know that the

larger the natural area, the greater the diversity and quality of ecological

functions the area can support.” Evaluation criteria include both landscape and

site level variables (Bergsma, 1999).

Examples of site level criteria include rare species, absence of

disturbance and regeneration while connectivity and wildlife habitat relate

more to the landscape level.

To develop the framework, we reviewed other

municipal natural area studies (Bergsma, 1999; CCL, 1993; Westworth, 2001), and

particularly the NOSS (City of Ottawa, 1998) and NESS (Region of

Ottawa-Carleton, 1997).

Because of the difference in scope between

the NOSS (City of Ottawa, 1998) and the Urban Natural Areas Environmental

Evaluation Study, many of the evaluation criteria used in the NOSS were not

applicable. These included criteria

pertaining to social values, recreational linkages, watercourses and protection

feasibility. The evaluation criteria

for woodlands and wetlands were quite similar in both studies, although they

were separated in NOSS, while they were combined in the Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study.

The main differences between NOSS and the

Urban Natural Environmental Evaluation Areas Study exist in the application of

the criteria and the thresholds used.

For example, in the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study,

the representative flora criteria examines degree of naturalness and species

diversity in a more quantitative manner than the species diversity criteria for

woodlands in the NOSS. On the other

hand, the absence of disturbance criterion was handled less quantitatively in

the Urban Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study than the NOSS. In the Urban Natural Areas Environmental

Evaluation Study, ecological functions were addressed under separate criteria

such as wildlife habitat, connectivity and habitat maturity while in the NOSS

ecological function was a stand-alone criterion. Connectivity is one of the nine evaluation criteria in the Urban

Natural Areas Environmental Evaluation Study, while in the NOSS there is a

separate specific analysis of ecological corridor criteria. The size criterion in the Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study also includes an analysis of the shape of the

natural area. The rarity of woodland

community types was not a separate evaluation criterion in the Urban Natural

Areas Environmental Evaluation Study as it was in the NOSS.

The UNAEES criteria utilize the NESS

principles such as ecological condition, habitat representation, special

features values and wildlife corridor capacity, but have been adapted to

accommodate sites that may potentially be found in a more urban setting. Similar criteria were used by CCL (1993) for

an evaluation of City of Waterloo’s woodlands.

Their five criteria were size, ecological age, habitat diversity,

species (floral) richness and significant species.

Once the evaluation criteria were selected,

there were several key decisions to make including the measuring and scoring

thresholds of each criteria, how many different points there would be for each

criterion, and whether to weight criteria in determining an overall rating for

each urban natural area. The NOSS used

three levels for each criterion in their evaluation framework. However, based on the team’s field

experience and knowledge of natural areas within Ottawa, it was thought that it

would be possible to discriminate more finely in this study. It was therefore decided that the evaluation

framework would include five points for each criterion. These ranged from 5 for high (or most

positive) to 1 for low (or most negative).

We recognize that not all ecological criteria

are equal in importance. However, we

also recognize that it is difficult to quantify these differences in any

meaningful way. We have thus not

attempted to weight the criteria.

Prior to beginning the fieldwork component,

the draft evaluation framework was presented to the Steering Committee, Public

Advisory Committee and at the public open house sessions in the spring of

2004. Several helpful comments on the

individual evaluation criterion were received and incorporated into the

evaluation framework for the field season.

The nine evaluation criteria are described

below, including a definition of the criterion and the thresholds used to give

a 1 through 5 rating for each. In many

cases the thresholds were altered based on the actual fieldwork findings in

order to capture the full range of quality found in the urban area. For example, the thresholds for the size and

shape criterion were modified to cover a broader range of natural area sizes. Instead of the highest score assigned to a

natural area with a size greater than ten hectares, based on initial review of

the findings, the threshold to receive the highest score was increased to

greater than twenty hectares. For the

representative flora criterion, the threshold to achieve the highest score was

decreased to 4.25 from 4.5 after a review of the initial data.

The challenge for the

UNAEES was to provide a comparative environmental evaluation that was standard for all sites, which rated each site on the basis of facts from fieldwork that was reliable, and produced results that can be

replicated. The

evaluation approach adopted by this study is easily repeatable, transparent and

permits re-evaluation under different scenarios such as a change in the scoring

threshold for an evaluation criterion or site alterations in the urban natural

area. However, it is designed to be

used by experienced professional investigators with expertise in ecology.

Evaluation Criterion 1 - Connectivity

Definition:

Linkages to other urban natural areas such as woodlots, watercourse

corridors and wetlands provide corridors for movement and assist in maintaining

the health of natural communities including diversity and genetic health. The connectivity rating also considers restoration

potential and opportunities for site and feature renewal and enhancement. Connectivity is not solely addressing the

physical connection between natural areas, but also evaluates the value of the

ecological function active between the natural areas. This criterion is an example of the evaluation considering the

ecological functions at a landscape level (Bergsma, 1999). When scoring the connectivity criterion the

features and functions of the natural areas that are connected were considered

along with the type of habitat within the linkage itself and the character of

the surrounding land.

|

Rating

|

Connectivity Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Other natural features, such as UNAs, greenbelt and waterway corridors, are

found in proximity to the evaluated urban natural area and the other natural

features possess a variety of positive functions. The connecting corridors are generally in a natural,

undisturbed state

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Other natural features, such as UNAs, greenbelt and waterway corridors,

have a diverse, sustainable character, however the corridors have some

disturbance and/or the natural features are further from the evaluated urban

natural area

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Some natural features, such as UNAs, greenbelt and waterway corridors, in

proximity to the evaluated urban natural area, but corridors show a higher

level of disturbance or natural features are limited in function

|

|

2

|

Isolated

|

Natural features in the vicinity of the urban natural area are limited and

linkages to these features are highly disturbed

|

|

1

|

Severely

Isolated

|

No other natural features of note within one kilometre of the urban

natural area

|

Evaluation Criterion 2 – Absence

of Disturbance

Definition: Physical disturbance within habitats significantly reduces native

biodiversity, the quality of ecological functions and ecological integrity

within natural habitats. The physical condition

of the area is a good indicator of overall natural quality and

significance. Examples of serious

disturbances in urban natural areas include the invasion of non-native plants

(herbaceous and woody), the fragmentation of woodland canopies by silvicultural

tree removal, power line right-of-way and roadways, tree forts and fire pits,

trails, dumping of organic yard waste and/or inorganic garbage, direct

encroachment into the natural area by adjacent landowners, and alterations to

surface or ground water functions. The impact of invasive plants was found to

be a major ecological challenge for many urban natural areas. The evaluation of

this factor differentiates between the simple presence of invasives and a

condition when the invasive species significantly affect natural functions of

the area.

|

Rating

|

Absence of

Disturbance Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

No notable disturbances observed in the urban natural area and potential

for affects from adjacent land uses are limited

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Only disturbances noted are minor and likely of short duration; few

invasive species, none of which dominate.

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Some disturbances are present but the ecological functions of the urban

natural area are not noticeably affected by the on-site and adjacent

disturbances; few invasive species with only local impact on native

vegetation

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

The disturbances are notable either in the area of the disturbance or the severity

of the impact on the ecological functions of the urban natural area; invasive

species common and/or with major impact in the majority of the area

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

Both the area of disturbances and the severity of the impact are

significant; invasive species common and having substantial impact throughout

the site

|

Evaluation Criterion 3 - Habitat Maturity

Definition: Although optimal conditions include a good

distribution and mixture of habitats at various ages, more mature habitats are generally

less common, less disturbed, much more difficult to replace due to their time

dependence (CCL, 1993), and contain a greater number of more valuable

functions. The age structure of the

natural area is a reflection of the land use pattern and history. This factor also considers that some species

and ecological functions are maintained only in mature habitats. This criterion is an example of the

evaluation considering the ecological functions at a community level (Bergsma,

1999).

|

Rating

|

Habitat Maturity

Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Urban natural area contains woodlots greater than 100 years old or other

habitats such wetlands, alvars and prairie habitat in an undisturbed, mature

condition

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Urban natural area contains a good representation of tree stands greater

than 100 years old or other habitats in an undisturbed, mature condition, but

notable portions of the urban natural area are less mature

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Urban natural area contains woodlots between 50 and 100 years old or other

habitats in an intermediate successional condition

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

Urban natural area contains a good representation of tree stands between 50

and 100 years old or other habitats in an intermediate successional

condition, but notable portions of the urban natural area are reflective of

early successional habitat

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

Woodlots within the urban natural area are less than 50 years old and/or

other habitats are highly disturbed and at an early successional stage

|

Evaluation Criterion 4 - Natural Communities

Definition: A greater number of natural community types and habitats should result in more diverse and

ecologically important natural heritage functions. A greater number of communities provide the environment for more

and different species within the ecosystem (CCL, 1993). Examples of the potential types include four

wetland habitats (swamp, marsh, fen and bog), and combinations of upland and

lowland forest habitat with deciduous, mixed and coniferous communities. More disturbed habitat such as cultural

meadows and thickets were not included in the analysis of this factor.

|

Rating

|

Natural Communities

Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Urban natural areas with greater than nine natural communities

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Urban natural areas with between seven and nine natural communities

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Urban natural areas with between four and six natural communities

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

Urban natural areas with two or three natural communities

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

Urban natural areas with one natural community

|

Evaluation Criterion 5 - Regeneration

Definition: The extent of

natural regeneration of canopy trees is indicative of a healthy,

self-sustaining urban natural area. A

number of factors can negatively affect regeneration, including presence of

invasive non-native species or prevalence of species typical of open/edge

conditions, soil compaction, and changes in soil moisture and light regime

(City of Ottawa, 1998). This criterion

is an example of the evaluation considering the ecological functions at a community

level (Bergsma, 1999).

|

Rating

|

Regeneration Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Regeneration of canopy tree species is high, as indicated by the dominance

and high density of seedlings and saplings of canopy tree species in the

understorey

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Seedlings and saplings of canopy tree species are not dominant in the

understorey, but are well established.

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Fair regeneration of canopy tree species, as indicated by some coverage of

seedlings and saplings of canopy tree species in the understorey, but the

density of regenerating stems is lower

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

Wooded areas with limited regeneration of canopy tree species and soil

conditions would suggest greater regeneration should be present. Non-native shrub species may dominate the understorey

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

No notable regeneration or factor not applied to urban natural areas

without wooded areas

|

Evaluation Criterion 6 - Representative Flora

Definition: Species of higher coefficient of conservation and a lower tolerance to

disturbances are generally good indicators of areas with less disturbance,

greater biodiversity and more ecological functions. Richness and diversity are valued as indicators of ecological

persistence and stability (CCL, 1993).

The coefficient of conservation identifies southern Ontario

plants requiring a high degree of naturalness.

Plants with a coefficient of

conservation value greater than 6 generally indicate a high level of naturalness

associated with the area and therefore it is likely that species of

significance are present. At least

thirty-five native plant species must be documented from a site to produce a

meaningful mean coefficient of conservation value. This criterion is an example of the

evaluation considering the ecological functions at a species level (Bergsma,

1999).

|

Rating

|

Representative Flora Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Mean coefficient of conservation is greater than 4.25 or 25 percent of the

native species with a coefficient of conservation greater than 6

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Mean coefficient of conservation is between 3.75 and 4.25 or 20 percent of

the native species with a coefficient of conservation greater than 6

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Mean coefficient of conservation is between 3.5 and 3.75 or 15 percent of

the native species with a coefficient of conservation greater than 6

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

Mean coefficient of conservation is between 3 and 3.5 or 10 percent of the

native species with a coefficient of conservation greater than 6

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

Mean coefficient of conservation is less than 3

|

Evaluation Criterion 7 - Significant Flora and Fauna

Definition: Such species are rare

in occurrence (ten or fewer contemporary populations documented within the City

of Ottawa) and/or ecologically important species are generally found in less

disturbed urban natural areas or those areas with greater rehabilitation

potential. These species are excellent

indicators of a high level of naturalness and natural diversity. The species used in this factor are native

flora and fauna, and usually need relatively pristine conditions. The updated treatment of the regionally rare

native plant list constitutes Appendix A of this study. The preliminary list of Brownell and Larson

(1995) was employed to identify regionally rare fauna.

Provincially rare species were those identified by the Natural Heritage

Information Centre with a SRANK of SH, SX, S1, S1S2, S2, S2S3, S3 or S3S4,

including any species endangered in Ontario as per the Endangered Species Act

and species noted as provincially significant in the 3rd Edition of

the Wetland Evaluation Manual (OMNR, 1993).

Nationally rare species are those listed as rare in Canada by Argus and

Pryer (1990) or listed as vulnerable, threatened or endangered in Canada by the

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

The Species At Risk Act (SARA) which came

into effect early in 2004 requires that protection consideration be given where

federal lands and waters are involved for any floral or faunal taxa listed

[see: http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/species/default_e.cfm].

There are, however, no floral or faunal species, be they regulated SARA taxa

(Schedule 1) or COSEWIC-designated candidates for SARA protection (Schedules 2

and 3), observed on the federal land examined

during this study.

|

Rating

|

Significant Flora and Fauna Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

A nationally rare species or two provincially rare species or more than

five regionally rare species

|

|

4

|

Good

|

A provincially rare species or four or five regionally rare species

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Two or three regionally rare species, but no nationally or provincially

rare species

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

No nationally or provincially rare species found and one regionally rare

species

|

|

1

|

None

|

No nationally, provincially or regionally rare species found

|

Evaluation Criterion 8 - Size and Shape

Definition: The area of the

urban natural area often affects the diversity and value of the ecological functions

that the urban natural area can support.

For example, larger woodlands provide more interior habitat than small

stands. In the moderately sized sites,

the shape of the urban natural area is also considered in this factor, as shape

determines the extent of wooded edge relative to the overall ecological

performance. Ecological persistence and

stability tends to increase with size (CCL, 1993). A greater amount of edge habitat in a linear natural area,

although potentially increasing the diversity of available habitat also

increases the opportunities for disturbance (CCL, 1993). Small areas, in the range of 1 hectare can

support common mammals such as muskrats, some forest birds (e.g. black-capped

chickadee and eastern wood pewee) and common amphibians such as green frog and

painted turtle (OMNR, 1999). At four

hectares common edge birds such as downy woodpecker and great crested

flycatcher can be supported, while at ten hectares there is potential for small

areas of forest interior habitat. Four

hectares is often used as the minimal size for functional woodlands (Riley and

Mohr, 1994).

|

Rating

|

Size and Shape Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Urban natural area is greater than twenty hectares in area

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Urban natural area is between ten and twenty hectares in area

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Urban natural area is between six and ten hectares in area

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

Urban natural area is between two and six hectares in area, or less than ten

hectares but with a linear shape

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

Urban natural area is less than two hectares in area

|

Evaluation Criterion 9 - Wildlife Habitat

Definition: This

ecological function considers high quality habitat and exceptional faunal characteristics

such as interior habitat and seasonal wildlife concentrations. Interior habitat is less disturbed and

supports disturbance-intolerant ecological features and assets, including rare

species and edge sensitive woodland species that are not tolerant of the

conditions found along the edges of woods. One

hundred metres from a natural habitat edge such as a forest edge or undisturbed

wetland was considered a more realistic characterization of the interior

habitat given the generally urban nature of the study area. (In studies with larger scale landscapes,

such as the Carp River Watershed Subwatershed Study, a factor of two hundred

metres was used). Areas supporting exceptional numbers of particular wildlife

species or function, such as breeding waterfowl, migratory bird staging areas,

or winter roosting and feeding areas for raptors (hawks and owls), constitute

rare natural features within urban landscapes and provide an important

ecological contribution. Similarly, areas functioning as components of wildlife

corridors contribute to both a greater degree of internal and external natural

rehabilitation, restoration and recruitment potential. They thus provide

greater ecological durability for both on-site and connected natural habitats.

This criterion is an example of the evaluation considering the

ecological functions at the landscape, community and species level (Bergsma,

1999).

|

Rating

|

Wildlife Habitat Criterion

|

|

5

|

Excellent

|

Contains more than ten hectares of interior habitat or is critical habitat

for seasonal wildlife concentration

|

|

4

|

Good

|

Contains some interior habitat or provides important habitat for seasonal wildlife

concentrations or rare or uncommon wildlife, or contains significant wildlife

corridors

|

|

3

|

Moderate

|

Provides some seasonal wildlife habitat such as wintering raptors,

waterfowl nesting, bird migration, unique breeding areas including raptor

habitat, cavity nesters or minor denning sites, or provide some wildlife

corridor function

|

|

2

|

Limited

|

Potential for some notable wildlife habitat

|

|

1

|

Poor

|

No particular wildlife habitat attributes

|

3.2 Landowner

Permission

In early 2003, the City’s Surveys and

Mapping Unit provided a database of information to the Project Team, linking

property ownership of candidate natural feature areas and the property boundary

mapping work. Of the 187 urban natural

areas, fifty-seven are City owned, fifty-one are privately owned, and

twenty-seven are owned by other public agencies including the Provincial and

Federal Governments and the NCC. The final fifty-two areas have mixed

ownership, with some parcels owned privately and other parcels owned by public

agencies.

Using this information, both public and

private landowners were initially contacted about the Urban Natural Areas

Environmental Evaluation Study.

Property owners were sent a letter in early May 2003 from the City, notifying

them that their property had been identified as having a natural area of

interest. Also through this letter, the

City requested permission to access their property in order that the field

biologist could visit and record observations on the identified natural

feature. A separate permission form

accompanied the letter and owners were asked to sign off on whether they would

grant or deny property access. This

mail-out package also included the first Study Bulletin, which provided an

overview of the study, its objectives, and a request for public participation.

Efforts were made to send only one letter

and permission form to individuals or organizations that owned more than one

parcel of land that was being considered for evaluation (e.g., NCC, school

boards, developers).

In the weeks that followed, signed

permission forms were sent back to City of Ottawa staff for processing. The access information was matched up with

the natural area of interest and provided to the biologist so he know which

areas he had permission to visit and for which ones permission to access had

been denied. Special instructions

received from the landowners, such as to call ahead of the field survey, were

passed along to the biologist as well.

In some cases, no permission form was returned to the City, or the