A Report From

The Bay Ward Task Force

On

Social Issues

On

Social Issues

Fall

2004

Fall

2004

The Bay Ward Task Force

On

Social Issues

On

Social Issues

Fall

2004

Fall

2004

Table of

Contents

Task Force Process and Participation

The Social Context

– An Overview of Bay Ward at the Turn of the Century

The Changing Ethnic and Cultural Mix of Bay

Ward

Work, Education and Income in Bay Ward

Issues Faced by Seniors and Programs to

Address Them

Issues Faced by Youth and Programs to

Address Them

Issues Related to Poverty and Low Incomes

and Adjustment to the Community

Our Conclusions and

Recommendations

Overview:

The Need for Community Development

Issues Faced by Seniors and Programs to

Address Them

Issues Faced by Youth and Programs to

Address Them

Issues Related to Poverty and Low Incomes

and Adjustment to the Community

Where Do We Go From

Here? A statement by the Councillor:

Summary of Task Force Recommendations:

Appendix A: Members of the Task Force

Appendix B:

Demographic Data for Bay Ward

Appendix C:

Materials Reviewed by the Task Force

Appendix D: List of Written Presentations

Appendix E:

Youth Crime Prevention through Social Development. Background Information and Examples

Appendix F: Some Examples of Interesting and Innovative

Activities in Other Communities

Appendix G: The Personal Security Index

Appendix H: Bay Ward Crime and Justice Statistics

In 2003 Bay

Ward Councillor Alex Cullen conducted a community consultation exercise called Building

Better Neighbourhoods In Bay Ward, which was designed to ask people in the

community what the City of Ottawa could be doing to improve the quality of life

in our neighbourhoods and communities.

The initiative for this exercise came out of earlier public consultations around the direction the newly formed City of Ottawa would take, given its new responsibilities and new resources as a result of amalgamation in 2000. Soon after amalgamation the new City of Ottawa began a round of planning and public consultation designed to lay out future directions for the City’s growth and development over the next generation. This exercise began with the Mayor’s Smart Growth Summit in June of 2001 and continued with the Ottawa 20/20 planning exercise, with the long term goal being to use the energy and resources of the new city to respond to the challenges of growth in a way that would maximize the quality of life for Ottawa residents. In April 2003 City Council adopted a number of the Ottawa 20/20 plans, ranging from the new Official Plan to the Human Services Plan, Arts & Heritage Plan, Economic Strategy, Water/Waste Water Management Plan, and others.

From the Ottawa 20/20

Exercise:

The creation of the amalgamated City of Ottawa in January 2001 brought 11 urban and rural municipalities and the regional municipality together in one government structure, responsible for providing services to a population of about 800,000. Over the next 20 years, the city's population will push past the one million mark and possibly reach 1.2 million. Employment growth is also expected to be robust over the coming years. The city's job base is expected to grow by about 250,000 by 2021.

This level of growth will open new opportunities for the city and its residents, but will also bring enormous change and new challenges. The question is, what shape will this change take? Will we follow the development patterns established in the past or will the advent of a new city require a new approach to city-building?

There are many reasons we cannot follow the growth patterns of years past. First of all, Ottawa has grown from a modest city on the banks of the Ottawa River to a large, complex and diverse urban region. Development patterns that were suitable for a small city are not necessarily appropriate for a large metropolis.

The Ottawa 20/20 exercise set out a blueprint for where the City could be in 20 years. The Building Better Neighbourhoods exercise was designed to move from “thinking globally” at the new City to “acting locally” in the neighbourhoods in Bay Ward.

What we were looking for in that exercise was developing a list of suggestions about specific physical improvements that the City could undertake on behalf of its residents in Bay Ward, improvements that would improve the quality of their lives – play structures, stop signs, changes in traffic flow through their communities.

The

exercise Building Better

Neighbourhoods

was a great success, both in the number of people who participated, and in the

range and quality of suggestions that were made. Roughly 125 people participated directly in 6 community sessions

in the spring of 2003, and their suggestions were incorporated into a report

which went to the City’s Health, Recreation & Social Services Committee and

City Council and on to City staff to act on.

Even with the current budgetary restrictions the City finds itself in,

some of these ideas are now being used to decide how the available spending on

capital projects in our ward will be done.

The Ottawa

20/20 exercise set out a blueprint for where the City could be in 20 years, but

at a high level of planning. The Building Better Neighbourhoods in Bay Ward exercise was

designed to move from “thinking globally” at the new City to “acting locally”

in the neighbourhoods in Bay Ward.

What we

were looking for in that exercise was developing a list of suggestions about

specific physical improvements that the City could undertake on behalf of its

residents in Bay Ward, initiatives that would improve the quality of life –

play structures, stop signs, changes in traffic flow through communities.

The Building Better Neighbourhoods exercise was a

success, both in the number of people who participated and in the range and

quality of suggestions. Some 125 people participated directly in 6 community

sessions in the Spring of 2003, and their suggestions were incorporated into a

report that went to the City’s Health, Recreation & Social Services

Committee, City Council and to City staff for inclusion in their workplans.

While we

were gratified with the number and quality of suggestions and with the

enthusiasm of the participants, we found that sometimes public events gain a

life of their own, and that people who came out to our sessions and who faxed,

e-mailed and mailed their suggestions to us had a range of suggestions that did

not fit easily in the framework that we had started with.

We heard

during that exercise about what we began to refer to as “softer” services (to

distinguish them from the list of desirable “hard” services that we had

envisaged in our original plan for the Building Better Neighbourhoods exercise.)

In fact, people came to these sessions with a range of social issues and

concerns – including gaps in recreational programming, about the need for

community development, about public safety and security, and about gaps in

supports to seniors.

Residents expressed concerns about increasing traffic and noise, graffiti and car theft, and pedestrian safety and security (particularly in the social housing communities). Service providers identified gaps in children and youth programming (particularly in Bayshore), and both service providers and seniors identified the need for support services for seniors aging in place. As well, cultural issues, including the need for better communication and understanding between established groups and new Canadians, was identified as an important issue.

This

prompted me to consider taking a more focussed, deliberative approach to

looking at these social issues and concerns, through a task force composed of

residents and service providers in Bay Ward. As a

result, in the Spring

of 2004, I presented this concept to the Bay Ward Council (a regular meeting of

Bay Ward community associations and the City Councillor to discuss local and

City Hall issues), which produced an improved version of our planned

consultation. As a result I asked a

number of people to join with me in a consultation exercise to examine social

issues important in our Ward, with an eye to understanding these issues and

recommending ways to address them. From this the Bay Ward Task Force on Social Issues was born.

In forming

the Task Force I wanted to take advantage of the experience and expertise of

local service providers, leavened with community representatives that would

represent the diversity of our Ward, all within a manageable number. I was

fortunate to be able to recruit a team of dedicated volunteers who were so

committed to the goals of this exercise. The names of the Task Force members

are listed in Appendix A. Together with

my staff they were instrumental in carrying off a highly successful community

consultation exercise which consisted of a series of community meetings,

intensive discussions among the Task Force members, the examination of a number

of background documents (see Appendix B), and the submission of a number of

excellent presentations from community members.

The Task

Force began its work in April 2004, meeting through the months of May, June and

in September of 2004. As well, the Task Force held three public meetings to

elicit community ideas and concerns – at the Carling wood Library on May 26

(from 4 to 6 pm); at Pinecrest-Queensway Health & Community Services on May

26 (from 7 to 9 pm); and at the Bayshore Field House on May 27 (from 7 to 9

pm). A listing of the written briefs provided to the Task Force during this

public consultation is listed in Appendix C. A draft report on the Task Force’s

findings was presented to the Bay Ward Council on October 6, 2004.

What

follows is a record of that exercise, some background information to put the

issues in context, and a list of recommendations which has emerged. These recommendations will form the basis of

a report to City Council which should help to raise awareness of the type and

range of social issues that residents of Bay Ward face and which will help me

and other policymakers, both at City Council and elsewhere, to set priorities

in the next budget and beyond.

It is worth

noting that what emerged most strongly from the consultation exercise, aside

from specific suggestions about how to address social issues, was the

perspective that Bay Ward (and Ottawa as a whole) is a community in transition,

with all the social issues and problems that is carried with it. Some of the issues would be familiar to

anyone who has followed the development of the West End of Ottawa in recent

years. Bay Ward has been, and continues

to be, for instance, the home of one of the largest concentrations of senior

citizens in Ottawa, and issues related to seniors will rank high in any

discussion of social issues in Ottawa’s West End.

But there

are some issues which are new and probably would not have been raised even a

few years ago, because the face of our community has begun to change. In a few years, different issues may arise. It is clear that our ability to deal with

social change in our communities, now and in the future, depends on being able

to address issues as a community, to identify our strengths as well as our

problems, and work as a community to bring resources to bear on our problems.

The social issues we heard about in our consultation exercise have their basis in the fact that Bay Ward is now one of the most diverse communities in the Ottawa area. It is also one of the fastest changing areas, putting pressure on every social agency and every community. In the same way that many of the issues we were told about would likely not have arisen in the same way as recently as 10-15 years ago, a scan of the ward offers a snapshot that looks quite different than a similar scan would have looked 15 or even 10 years ago.

Among the characteristics that have changed in Bay Ward are the ethnic and cultural makeup of its population, general demographics of its population, the kinds of jobs that people do to make a living and their resultant incomes, where and how they live, and how they interact with each other. These changes, of course, have happened at the same time as Ottawa, and Canada as a whole, have been changing. However, some of the changes have happened more quickly, and are more pronounced, than for Ottawa as a whole. The resultant pressure on our social agencies and on the life of our communities was obvious during our consultation sessions.

In a recent publication the United Way of Ottawa did a snapshot of the city’s changing demographics, and discussed the significance for Ottawa and its social service agencies of an aging population.[1]

The United Way’s

analysis found that Ottawa is an aging society. Over 11% of people living in Ottawa are aged 65 and over, and the

number is expected to double by 2008.

As the United Way notes, the significance of this figure, and this

trend, is that it will put pressure on every social service agency in the City,

because seniors are more likely to experience disabilities, both physical and

mental, will need more medical help, more care from specialized agencies in the

community, and are also more likely to live in low income situations than

younger age groups. As the United Way

noted, research suggests that seniors are more likely to need health care than

younger people, which is reflected in the fact that they consumed roughly 41%

of health care costs in 2000-2001, though only making up about 11-12% of the

population. Further, as the study

noted, “most seniors have at least one chronic health condition, the most

common being arthritis and rheumatism, and are expected to experience some form

of mental, physical or sensorial disability”.

The United Way’s

analysis found that Ottawa is an aging society. Over 11% of people living in Ottawa are aged 65 and over, and the

number is expected to double by 2008.

As the United Way notes, the significance of this figure, and this

trend, is that it will put pressure on every social service agency in the City,

because seniors are more likely to experience disabilities, both physical and

mental, will need more medical help, more care from specialized agencies in the

community, and are also more likely to live in low income situations than

younger age groups. As the United Way

noted, research suggests that seniors are more likely to need health care than

younger people, which is reflected in the fact that they consumed roughly 41%

of health care costs in 2000-2001, though only making up about 11-12% of the

population. Further, as the study

noted, “most seniors have at least one chronic health condition, the most

common being arthritis and rheumatism, and are expected to experience some form

of mental, physical or sensorial disability”.

The impact of this aging can be felt on the ability of families to care for aging members, on the supply of home care in the community, and in the need for a range of professional and volunteer services in order to keep seniors functioning in the community. These include help with housework, snow clearing and yard maintenance, and help with transportation for a wide range of activities, including those activities and facilities which reduce isolation and enable seniors to live healthy lifestyles.

It is worth noting that the percentage of Bay Ward’s population that is aged 65 or older is, in fact, approaching double that of Ottawa as a whole. Some 21% of the Bay Ward population are senior citizens.

If an aging population represents a pressure for which Ottawa needs to plan, it should be noted that in Bay Ward the crisis in already upon us. As we were told during the consultation sessions, this crisis can be seen in the form of pressure on virtually every agency which serves the community.

In the past few years Ottawa has become, as the United Way has noted, “a community of great ethnic and cultural diversity”. Immigration is the main driver of population growth in Ottawa, and was responsible for just under 40% of our population growth between the last two census counts. The United Way and other agencies are expecting the immigrant share of our population to double by 2020, and is beginning to plan for the pressures and changes that this implies.

Among these pressures are the need to provide a wide range of specialized social services that are culturally sensitive. As the United Way notes, recent immigrants with university degrees, for instance, are four times more likely to be unemployed than longer term residents with similar qualifications. Those with skilled trades certification are much more likely to be either unemployed or working at a job that does not require their skills than those who have been here longer. And as a result of this and other pressures, the average weekly income of recent immigrants is significantly lower than for Canadian born residents.

All these factors put more pressure on social service agencies, on

the need for affordable housing, and on the need for training and counselling

services that meet the language and cultural needs of an increasingly diverse

community. The challenges faced by

recent immigrants can also be seen in a range of related issues. Immigrants are more likely to live in

crowded households, they are likely to spend a higher proportion of their

income on shelter, leaving less for other needs, and the problems of child

poverty are more apparent in recent immigrant families than in those who have

been here longer and are more established.

All these factors put more pressure on social service agencies, on

the need for affordable housing, and on the need for training and counselling

services that meet the language and cultural needs of an increasingly diverse

community. The challenges faced by

recent immigrants can also be seen in a range of related issues. Immigrants are more likely to live in

crowded households, they are likely to spend a higher proportion of their

income on shelter, leaving less for other needs, and the problems of child

poverty are more apparent in recent immigrant families than in those who have

been here longer and are more established.

If these trends represent a wakeup call for Ottawa’s social service agencies, who are feeling the pressure of meeting growing and changing needs, it should be noted that the pressures are even more intense in Bay Ward. Consider, for instance, the fact that while visible minorities make up roughly 18% of the Ottawa population, they make up 27% of the population of Bay Ward.

Bay Ward has now become one of the most diverse communities in

Ottawa, with the resultant pressure on a range of social services and

agencies. While just under 20% of the

population of Ottawa speak a mother tongue other than English or French (up

from just over 17% in 1996) that number is just under 30% in Bay Ward (up from

26% in 1996). The resultant pressure on

our social agencies was one of the major themes of our consultation sessions.

Bay Ward has now become one of the most diverse communities in

Ottawa, with the resultant pressure on a range of social services and

agencies. While just under 20% of the

population of Ottawa speak a mother tongue other than English or French (up

from just over 17% in 1996) that number is just under 30% in Bay Ward (up from

26% in 1996). The resultant pressure on

our social agencies was one of the major themes of our consultation sessions.

Just as significantly, the number of people who can function in

neither official language, and therefore face major problems in accessing

services, and who need special assistance from the social service agencies in

our community for a range of health, social and recreational and economic

needs, is growing, and growing faster in Bay Ward than in other parts of

Ottawa.

Just as significantly, the number of people who can function in

neither official language, and therefore face major problems in accessing

services, and who need special assistance from the social service agencies in

our community for a range of health, social and recreational and economic

needs, is growing, and growing faster in Bay Ward than in other parts of

Ottawa.

While roughly 1.4% of the population of Ottawa speaks neither official language, a statistic that did not change between the last two census counts, the proportion in Bay Ward went from 2% in the 1996 census to 2.6% in 2001. The resultant pressure on the services in our community is more obvious in Bay Ward than most of the rest of Ottawa.

The pressures on social agencies and facilities in our community can also be seen in the statistics on work and education in Bay Ward.

As the United Way study notes, while the median income in Ottawa is

well above the level for Canada as a whole, and while unemployment is lower

than for Canada as a whole, Ottawa is not immune to the problems of

unemployment. These problems are more

severe for those with less education.

They are more severe for new Canadians than for those more established,

because of problems with recognition of foreign credentials. As the United Way notes: “There are still

more than 30,000 workers every month who are actively seeking employment”. A larger than proportional share of these are

contained in Bay Ward, as well as a larger than proportional share of those who

have given up looking and are no longer in the labour force.

As the United Way study notes, while the median income in Ottawa is

well above the level for Canada as a whole, and while unemployment is lower

than for Canada as a whole, Ottawa is not immune to the problems of

unemployment. These problems are more

severe for those with less education.

They are more severe for new Canadians than for those more established,

because of problems with recognition of foreign credentials. As the United Way notes: “There are still

more than 30,000 workers every month who are actively seeking employment”. A larger than proportional share of these are

contained in Bay Ward, as well as a larger than proportional share of those who

have given up looking and are no longer in the labour force.

Perhaps the clearest indication that the problems of work and income are more severe in Bay Ward than for Ottawa as a whole is the fact that people in Bay Ward make a lower proportion of their income from employment, and a higher proportion from government transfer payments of all kinds, than for Ottawa as a whole. While people in Ottawa as a whole get just a little over 7% of their income from government transfers, in Bay Ward that number is just under 13%.

No wonder then that the significance of low incomes is felt more

strongly in Bay Ward than in most of Ottawa. While about 15% of the population

in Ottawa was classified in the last census as “low income” (meaning that they fell below the Statistics

Canada Low Income Cutoff line), in Bay Ward the proportion was 22%. For families, the proportion falling below

the Low Income cutoffs was 11% in Ottawa as a whole, but increases to just

under 18% for Bay Ward. The impact of

these numbers on social agencies and the services they provide, on the need for

affordable housing, and on community agencies (like food banks) is obvious.

No wonder then that the significance of low incomes is felt more

strongly in Bay Ward than in most of Ottawa. While about 15% of the population

in Ottawa was classified in the last census as “low income” (meaning that they fell below the Statistics

Canada Low Income Cutoff line), in Bay Ward the proportion was 22%. For families, the proportion falling below

the Low Income cutoffs was 11% in Ottawa as a whole, but increases to just

under 18% for Bay Ward. The impact of

these numbers on social agencies and the services they provide, on the need for

affordable housing, and on community agencies (like food banks) is obvious.

As the United Way notes, “the link between affordable housing, hunger and healthy development, especially in our children, is connected to the level of income of individuals and families. In order for a community as a whole to prosper, it is necessary to work together to break down the barriers that contribute to the increasing disparity of life situations within our society.”

As we were told several times in our public consultations, the job of breaking down those barriers, in a society with a range of ethnic and cultural communities, high unemployment and low incomes, puts pressure on all our agencies and all our social services.

As the most recent census figures demonstrate, family life in Bay Ward is more likely to be lived in rented accommodation than in Ottawa as a whole. While Ottawa as a whole is a community of owners (61% of private accommodation in Ottawa as a whole in owned and 39% is rented) Bay Ward is largely a community of renters. 58% of the private accommodation in Bay Ward is rental, while 42% of it is owned.

These numbers, of course, reflect the hard facts of income and

employment in Bay Ward, which are less favourable than for Ottawa as a whole.

These numbers, of course, reflect the hard facts of income and

employment in Bay Ward, which are less favourable than for Ottawa as a whole.

As a result, shelter issues cut more sharply in Bay Ward than in most of other parts of Ottawa.

As only 7% of Bay Ward’s housing stock is social housing (i.e. socially-assisted or rent-geared-to-income housing), a considerable number of people living at or below the poverty line are in private rental situations, including a significant amount of seniors.

The proportion of tenants paying over 30% of their income on shelter (and who therefore have less income to spend on food, recreation, transportation, clothing and other necessities) is higher in Bay Ward (just under 39%) than in Ottawa as a whole (37% in the last census).

At least part of this can be seen in the fact that people in Bay Ward have benefited less from the economic prosperity of recent years as the high tech community in Ottawa expanded. People in Bay Ward benefited less from this economic good fortune than people in Ottawa as a whole because Bay has a higher proportion of people who depend on government assistance rather than employment income, and government assistance rates, by and large, unlike market income, has been virtually frozen since the late 1990s. The result is pressure on a range of social agencies, not least of which are the various agencies that deal with housing needs.

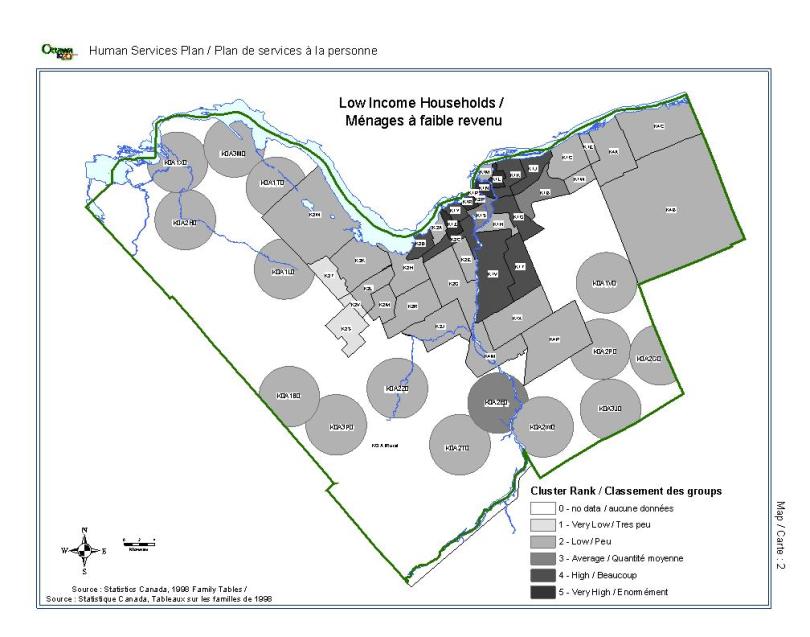

As the next image shows, the neighbourhoods of Bay Ward have a disproportionate share of the low income households in Ottawa.

As we were told in the

consultation sessions, they also have a disproportionate share of the social

pressures and issues that come from the presence of poverty and low incomes.

As we were told in the

consultation sessions, they also have a disproportionate share of the social

pressures and issues that come from the presence of poverty and low incomes.

It is significant to note that what the United Way says about poverty and family life in Ottawa is felt even more acutely in Bay Ward, where low incomes, employment related issues, problems with overcrowding and the lack of affordable housing, and a range of related social issues, are made more acute by the demographic pressures in the Ward, particularly aging, which are more acute than for Ottawa as a whole.

As the United Way notes in its recent environmental scan of social issues and statistics in Ottawa, all the detrimental effects of disparities in wealth and income, labour market difficulties, health and a range of associated social issues ultimately come down to the health of our families, which in turn determines our health as a community.

As the United Way notes, the studies connecting poor social and health outcomes with children growing up in poverty are legion. And while many studies document the increasing levels of stress on our families, especially low income families, those in low income situations are less likely to have the opportunity to relieve the stress. For example, access to activities that can improve socialization skills and feelings of self worth, such as leisure and recreational sports, has decreased. In Bay Ward, we were told, for instance, that the issue of access to such activities is acute across the Ward, but especially acute in the Bayshore area. This is a documented issue which awaits a solution, but when the solution is defined there is no doubt it will involve devoting more resources to the families and facilities in this area than is currently the case.

As the United Way study sums it up,

Poverty is detrimental to positive, healthy developmental outcomes for our society. Early childhood development casts a long shadow into adulthood in terms of educational outcomes, labour force attachment and overall adult health, both physical and mental. It has been estimated that ‘every dollar spent on early childhood development saves $7 in potential costs to the justice, social service and health care systems.’[2]

The study goes on to ask a number of pointed questions:

In one way or another, each of these questions was raised during the consultation sessions.

Two questions, which were also raised during the sessions, remain unanswered:

Our Task

Force held three public meetings: at the Carlingwood

Library on May 26 afternoon; at Pinecrest-Queensway Health and Community

Services on May 26 evening; and at the Bayshore Field House on May 27

evening. A number of people made written

submissions, some of which were presented at these meetings. In addition, a number of people spoke at the

meetings.

The concerns raised at the public meetings and in written presentations, and the concerns discussed by the Task Force members at their meetings, could be grouped into a number of broad themes. They include:

However, of the issues raised, four stand out, and together they incorporate the bulk of the comments that were made to the Task Force over the period of this consultation.

Some people felt that their neighbourhoods and communities are not as safe as they could be, and that more attention needs to be paid to issues of physical safety, crime prevention and the protection of persons and property. In particular were the concerns raised in Bay Ward’s Ottawa Community Housing neighbourhoods over safety and maintenance issues. Further, it also became clear that perception about safety and security concerns held by many in the community are themselves an issue that needs to be addressed since they make community development more difficult.

·

Issues

Faced by Seniors and Programs to Address Them

Due to increases in demand, support services for seniors in the Bay Ward community have become a concern. There is a sense that the ongoing pressures of an aging society will continue to make conditions worse until policymakers begin to focus on the issues and needs of seniors in the community. With the evolution of our community in recent years, a new dimension - services that are culturally sensitive - has also emerged.

·

Issues

Faced by Youth and Programs to Address Them

Although Bay Ward does not have the largest concentration of young people in the Ottawa area, the multicultural dimension and the fact that incomes are lower, on average, in Bay Ward than in Ottawa as a whole, makes the issue of programs for children and youth particularly important. During the earlier consultation sessions (Building Better Neighbourhoods) we were told that the physical infrastructure for recreation programs was just not there in the major parts of our community. During this round of consultations we were told that programming for youth in general is inadequate, and that this inadequacy goes beyond recreation to employment support and counselling, job creation, leadership training and skills development. We were told, as well, that this inadequacy is most sharply felt by new arrivals to the community.

·

Issues

Related to Poverty and Low Incomes and Adjustment to the Community

Bay Ward is a community which includes many people with low incomes; their needs range from affordable housing, employment related programs, health and family related services to a range of counselling and support programs, and programs to help new arrivals adjust, often in difficult economic circumstances. There is a general feeling that the level and quality of many of these programs has deteriorated in recent years, at a time when the need for them has, in many cases, become more acute. Many in the community feel their issues are being ignored, and they don’t necessarily feel as if they are part of the community. The issues are made more complex, and difficult, because these programs need to reflect the increasingly multicultural nature of our community.

Not every single issue that was raised with us during this consultation could be encompassed under these four broad themes, but most issues fall into one (or more) of these categories. They are the issues that were raised with us the most, and the most insistently.

None of these issue areas can be handled solely by the City – the City’s jurisdiction, its financial and staff resources and the many competing demands on its limited resources mean that while we can note these issues, and bring them to the attention of policy makers, the job of addressing them can begin with us but will not end with us.

In each of these areas, however, we can begin – by noting their importance, by trying to understand where the issues come from, and by trying to move them up the ladder of priorities at the City level, and ultimately at the Provincial and Federal levels as well, where resources are larger - even if awareness of the issues as they touch our neighbourhoods and communities is sometimes less acute.

What follows is a brief description of the issues as they were raised during our sessions, mostly in the form of brief quotes from comments made at the meetings or in written briefs, together with some information and material that touches on each of these issues and may be useful in putting them in perspective.

We have to break down the misperceptions that have been built about the members of our community. “Black kids” in cars does not immediately indicate car theft. Individuals living in social housing are not automatically lazy people. People are often unemployed because they can’t find jobs.

Richard Breakenridge

President, Britannia Woods Community Association

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

Most of today’s Somali immigrant youth in Ottawa came in the beginning of the 1990s as 6,7 and 8 year olds. When I came to this city, during that period of time, Ottawa used to be considered as one of the safest in Canada. Streets seemed to be safe and one could venture away from their home without thinking much about security and safety at all. For the last six years or so, security has been gradually sliding and reality of the city’s riding problems were all evident: gangs, racism and prejudice, criminal activities, and misperception have been leading the way.

Ibrahim Osman

Ottawa Somali Fathers Association

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

Police officers must be culturally sensitive to immigrant kids – especially to Somalis who continue to have the habit of gathering around on evenings and at nights at corner stores or other open areas for the pure reason of having a chat or some fun together. I believe they will eventually break the habit if we could be patient and hold frequent awareness sessions for them.

Ibrahim Osman

Ottawa Somali Fathers Association

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

We have conducted community safety audits in many Ottawa Housing sites and buildings across the City. Safety issues are huge on the agenda of residents. Many of the issues are directly related to the lack of maintenance and of a presence of security people from Ottawa Housing. The occasional drive through by security staff on many sites is simply not enough. There are many sites and buildings that are in crisis and need a full time on site security staff.

Wendy Byrne

West End Community Action Network (WECAN)

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

I have a strong belief in empowerment. Residents need to be brought together. We need something more than the current Neighbourhood Watch program; we need to organize to deal with public safety; we need to publicize incidents to attract and direct resources. People don’t know their neighbour, their community. People must take responsibility.

Geoffrey Sharpe

member of Ad Hoc Committee on Public Safety in Bay Ward

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

I’m concerned about youth gangs. Graffiti are a problem, and so are needles in the parks. I’m willing to work with the police. We need to communicate with other neighbourhoods.

Shirley Mosley

Bayshore resident

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

There is a need for crime prevention measures – youth drop-in centres, restorative justice programs, such as the pilot at Caldwell, called Youth in Conflict with the Law.

Tammy Corner

Michele Heights Community House Co-ordinator

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

The issues are youth crime, the state of social housing, drugs and prostitution in the community, and problems in getting a police presence in the community. Perhaps we could use the elementary schools to identify and help kids at risk; a good example of this is the program now in place at Severn School.

Sherril Noble

resident of Grenon Avenue

At the Carlingwood Library meeting, May 26

Seniors and Transportation

Many senior women never learned to drive or have given up or lost their drivers’ licenses at age 80. The latter is also true of senior men. If boarding a regular OC Transpo bus is difficult, they must depend on taxicabs (at roughly $30 per trip). A secondary issue regarding taxis is the need by seniors for assistance with walkers or canes that is not generally supplied by cab drivers.

The other source for transportation is volunteer drivers from community support agencies (Olde Forge Community Resource Centre or Nepean Seniors Home Support) which will cost roughly $8 to $15 per trip. Unfortunately, community support agencies are presently under funded by both the City of Ottawa and the provincial Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and also must depend on volunteers to provide both car and driver. Both agencies have more than 800 seniors dependent on them to provide drives to various medical appointments. Such agencies are unable to cope with the need for transportation to social and recreational activities. Both have very limited grocery bus service.

Comments are frequently made by some that seniors can turn to family for help. Some can and do but many cannot. Some seniors have outlived their children or children are in other cities or are working during the day and therefore not available.

ParaTranspo has had its funding frozen since 1996 and cannot cope with the growing demand from seniors and those with disabilities. While the service is both good and inexpensive, it can only be booked one day in advance and waits for service are frequently long and prove a difficulty to many seniors.

Seniors and Housing

Bay Ward has a considerable number of seniors living under or very close to the poverty line. Even those who have slightly higher incomes are seeing it eroded as the cost of food, rent, transportation, etc., climbs.

Subsidized housing is available in only two buildings in Bay Ward – 31 McEwen with 177 units and 2361 Regina which is an age-mix building with a decreasing number of seniors living there. This decrease is certainly due in part to concerns by seniors and their families for safety and security.

It has been reported by OCHC staff that 2651 Regina will become simply an adult building in a very short time. This will effectively reduce the number of subsidized units available to seniors in Bay Ward. This at a time when numbers of seniors is growing rapidly. The argument can be made that seniors can enter any OCHC building in Bay Ward but there is consensus among service providers that an all seniors building is the safest and most appropriate place for those over the age of 65.

Care in the Home

Two agencies provide a variety of in-home services to seniors in Bay Ward – the Olde Forge and Nepean Seniors Home Support. Both have client numbers in the area of 2,000 or more. The services offered include transportation to medical appointments, grocery bus service, home help (cleaning and some meal preparation) and home maintenance, foot care, telephone security, friendly visiting, meals on wheels and/or diners club, income tax assistance, and information and referral. Some services are free and others have a nominal fee.

Both agencies have been traditionally under funded and are limited by both financial and human resources in providing complete care to the elderly.

The Community Care Access Centre no longer provides homemaking which was a free service from CCAC and seniors must turn either to the community support or private home care services. Money is frequently an issue for seniors so they either do without or limit the assistance they require due to age or disability or both.

Seniors and Recreation

Bay Ward has no seniors’ centre. The Alex Dayton Kiwanian Seniors Activity Centre is not particularly popular among area seniors due in part to the fact that it operates more or less as a private club with fairly high fees charged. Most seniors in the area travel either to the Churchill Club or to Good Companions Seniors Centre both of which offer excellent programs to seniors. Or they go nowhere!

The Owl’s Nest was quite popular among local seniors and has been missed since its closure several years ago. Some seniors from that group now meet once a week at the Olde Forge but this is most inadequate. There is a very strong need for a local drop-in centre or central meeting place for seniors that would offer social and health-related activities.

Central to this requirement is the problem of transportation – not much point in opening a centre for seniors if they can’t get there! Location on a good bus route would be helpful but the issue of transportation must be considered.

From a submission by Barbara Lajeunesse

Executive Director of the Olde Forge

(There is) no doubt that the number of immigrant seniors in the West End is dramatically growing. A high percentage of these seniors can not handle themselves in most cases, and live under the care of their families due to cultural and ethical reasons. These caregivers are not paid for the work they do for these seniors and ultimately they have to stretch their time between work, household, kids and caring for their elderly.

Ibrahim Osman

Ottawa Somali Fathers Association

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

(We need) special facilities for senior immigrants who do not speak other than their language and who have culturally demanding needs. This may include a place where they can come and socialize with each other, where they can express their talents, such as crafts, embroidery, knitting etc.

Ibrahim Osman

Ottawa Somali Fathers Association

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

There is a need for seniors programs in Bayshore, for drop-in, conversation, socialization.

Ellen Toxopeus

Senior living in Bayshore

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

There is a need for facilities like the Jack Purcell Centre in the West End which can provide an exercise centre and warm pool for seniors and the physically challenged. And those on ODSP should get a reduced bus pass - transportation is a major problem for the poor & disabled and bars them from using programs and facilities.

Madeleine Legault

senior citizen from Glabar Park

At the Carlingwood Library meeting, May 26

We need for a west-end seniors centre that is close by, accessible, low cost, that would provide programming (bridge, outings, crafts, exercise classes, dance, speakers). We should re-establish the Owl’s Nest (a former Public Health drop-in centre for seniors at Lincoln Hts. Galleria).

Louise Fulford

member of the Churchill Club and Good Companions

At the Carlingwood Library meeting, May 26

There is a need for more home support and personal support services for seniors in the West End, but these support services require better co-ordination. The Council on Aging Vieillir chez soi model is a good one, and could be followed. Since there is a noted shortage of family doctors in the west end, one role for the Community Health Centres is to become centers of primary health care (i.e. 24/7 community clinics). There is also a shortage of mental health supports; the ACT program at PQHCS and Carlington HCS is overextended, and can only deal with crises.

Marlene Catterall

M.P. for Ottawa West-Nepean

At the Carlingwood Library meeting, May 26

Our community house has children and youth programs but the staff is not valued and the salaries are often substandard, part time, contractual and short lived. Due to this there is a high staff turnover. We must be able to build sustainable, meaningful relationships in order to make a real impact on our children and youth. Through these positive adult relationships the children and youth will feel more connection to their communities. This will build community pride and will replace the children’s need to gain connection elsewhere, like in gangs.

Richard Breakenridge

President of the Britannia Woods Community Association

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

Kids need more spaces for training centres and recreational activities as the old facilities in the neighbourhoods have gone outnumbered and mostly unrepaired. Without providing kids with these infrastructures, they would get astray and turn to other easily accessible things, such as drugs, criminal activities and bullying.

Ibrahim Osman

Ottawa Somali Fathers Association

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

A major issue is the lack of services for school age children – lack of recreational programming, after-four programs, etc. … The former Nepean had recreational programming; Minto programming has not replaced this. The City of Ottawa’s programs are not local (transportation is a problem) and accessibility is a problem due to fees.

Nicole Coghill

member of the Bayshore Community Association

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

A barrier to programming such as English as a Second Language classes is lack of onsite child care. Bayshore is very multicultural – Asian, Indian, Chinese, Arabic – highly skilled, but lacking in Canadian certification, therefore few jobs.

Nouria Issa

Nepean Community Resource Centre outreach worker

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

Why is there nothing for youth (age 11 to 22) in Bayshore? There’s no soccer league, no baseball. When school is closed there are no programs. It costs $100 to get a pass to the Exercise Room at the Bayshore Recreation Centre – this is unaffordable for kids. … The youth problem is boredom!

Ahab Elbarseigy

youth living in Bayshore

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

We do a lot of fundraising for activities such as conflict resolution, but we still need support. We need a youth worker, and we need long term funding to sustain this position.

Sharika Rahman

Bayshore Youth Council

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

We need long term funding to develop long term relationships and get more youth involved. The Youth Make It Happen program attracts 30 youth weekly; it won a United Way Community Builder Award; but its future is in doubt over future funding.

Kaireh Ismail

youth, resident of Michele Hts.

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

We need recreation programming for youth, particularly for ages 6 to 12. Fees are a barrier to access. Programs are better than youth drop-ins

Tammy

Corner

Michele Heights Community House Co-ordinator

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

Stable funding is an issue for youth programs if you want long lasting results. Longer programs build relationships, shorter programs have little impact, no matter how well designed. For instance, the Youth Make It Happen program was funded through the Trillium program and Crime Prevention grants for the past 3 years. It involved 2 youth workers in 5 communities, one day a week, at a cost of about $200,000. But the program is ending this summer. We also need an employment-subsidy program to create youth jobs. Current employment preparation programs as “How to Write your Resumé” are not adequate. The Pinecrest Queensway Youth Retail Program (funded through HRDC) has been very successful – but we need more participating businesses.

Nasir Mohammed & Khader Megan

youth from Foster Farm

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

Many individuals living in low income, being supported by Ontario Works would rather be working. It is almost impossible, even with affordable housing, to make ends meet. After we have purchased a bus pass, paid our Hydro and phone bills, there is barely enough left for food. There have to be new solutions for people in our community.

Richard Breakenridge

President of the Britannia Woods Community Association

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

There needs to be more assistance and support to individuals who want to start their own business so that they can gain control over their own futures. If we have healthier families, we will have healthier communities.

Richard Breakenridge

President of the Britannia Woods Community Association

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

We need to maintain the upkeep on the houses in our community. No one is going to take care of their unit if doorknobs are not replaced, ceilings are falling down, graffiti is not immediately taken down and if snow removal and landscaping is done at a substandard level.

Richard Breakenridge

President of the Britannia Woods Community Association

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

… chronic unemployment among adult Somalis living in the West End, making them feel useless despite their education, which eventually leads them to stress and being indifferent to their surroundings, even to their own families at times …

Ibrahim Osman

Ottawa Somali Fathers Association

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

The City of Ottawa (via Ottawa Community Housing) needs to place a priority on the creation of more units and needs to allocate funding from their budget to this end. It is also not helpful when occupied subsidized units are expropriated to create office space for the landlord, and this practice should be actively discouraged.

Wendy Byrne

West End Community Action Network (WECAN)

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

There is a need for the City to look at becoming involved in more creative partnerships, such as the development at Richardson/Byron with CCOC and CAHDCO (Centretown Affordable Housing Development Corporation) which has built housing that was sold at cost to those with a lower income. There are steps the City can take with regard to lowering or exempting development fees, etc. …

Wendy Byrne

West End Community Action Network (WECAN)

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

What many of these (affordable housing) sites and buildings also need are more on site community support for their residents to deal with a myriad of issues, from mental health issues to seniors being able to age in place. There should be more funding assistance … for community housing coordinators for all sites and buildings. … There needs to be more openness and action by the City to accessing other supports in the community – for example, the Olde Forge being on site in seniors’ buildings and age-mix buildings …

Wendy Byrne

West End Community Action Network (WECAN)

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

While ODSP (Ontario Disability Support Plan) is a provincially legislated program, it is administered by the City … minimum wage and social assistance rates are not adequate to allow individuals to cover the costs in meeting their daily needs. … The City can be of assistance by lobbying the Province to increase the rates. I believe the Province has made a start in this direction, however we need to ensure that rates are brought up to an acceptable level – to at least the poverty line.

Wendy Byrne

West End Community Action Network (WECAN)

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

There is the need for family programming as well as for youth. In my townhouse row of 8 units there are 6 ethnic groups. We need social events and community interaction to help people to know each other. There is a culture shock as well as a generation gap. Neither the City nor Minto are providing enough programs

Sahra Habani

Bayshore resident

At the Bayshore Field House meeting, May 27

We need more affordable housing, more adequate social assistance. The rates were cut 22% in 1995 and there have been no increases since. There is a problem of “feed the kids or pay the rent”. People on social assistance need steady, reliable jobs.

Cindy Bellehumeur

resident of Michele Heights

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

There is a lack of good quality childcare in west end – licensed, not-for-profit childcare. Lack of subsidized childcare is a problem for working parents and for children. Licensed childcare is based on early childhood education – a good investment. Every dollar invested in good childcare programs saves $5-$7 in future social costs. The National Child Benefit should not be clawed back from parents on social assistance – they need it the most. Ontario Works puts pressure on parents to seek training or jobs, but lack of good quality, licensed childcare is a barrier.

Joanne Roulston

resident of the community

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

We need more affordable housing, and we need to partner with non-profit groups. Maintenance is an issue (too many leaky roofs and basements). Social assistance rates are too low, and are unrealistic. There has been no increase since the 1995 cuts.

Tammy Corner

Michele Heights Community House Co-ordinator

At the PQHCS meeting, May 26

Affordable housing is an issue, but so are affordable bus passes. Regina Towers has a Salus social worker for mental health clients in building, but we need more services than Salus provides. People need to feel safe, important, and worthwhile.

Carol Smith

Regina Towers Tenants Association Executive

At the PQ meeting, May 26

In our consultations with members of the community we were told by a number of people that community development is a high priority in Bay Ward. We found few who would disagree. However, we discovered that the term “community development” can mean different things to different people.

In the appendices to this report we have included some background material on community development and some specific examples of community development that are worth looking at. There are many others that are not referred to in this brief document.

We also discovered, however, that there is actually a great deal of community development going on in Bay Ward, which is a good sign, but that it is being constrained and narrowed in its impact by funding issues and by jurisdictional issues. As well, not all community needs are the same.

There is a sense from the discussions we have been having and from the consultation sessions that we held that there was a time when the City of Ottawa took community development seriously but that it does not do so any more. Nobody could offer us any specific evidence for this, but the best evidence would be whether sufficient resources are being put into community development to achieve significant results in the face of the significant issues raised and the pressing demographic, economic and other issues outlined earlier in this report in our short snapshot of Bay Ward. There is a general consensus among the people we talked to that the answer to this question is clearly no.

However, the new City of Ottawa is now ideally situated to re-establish community development programs. With provincial downloading of responsibilities and amalgamation, the City now finds itself with responsibilities for housing, social services, public health, police, and recreation. It is now in a position to re-assess its support for community development in general, and to make better use of its existing resources. While the Bay Ward Task Force on Social Issues is focused on local concerns, its findings should help the City re-shape its community development programs.

Our first set of recommendations, then, has

to do with community development.

In particular, there is general agreement

that the community houses in the Ward are doing worthwhile work but that they

are seriously under funded. Their staff

resources are not always adequate to the large job they have to do.

To a certain extent, of course, any activity that addresses social issues constitutes a form of community building. This Task Force report, for instance, will allow members of the community to argue that certain problems have been identified and deserve to be addressed. While a Task Force such as this one cannot build capacity itself, it can form part of the process of showing people how to step up and ask for the resources they need to address their issues. This is what politicians listen to, and our job is to help our community express their needs in a way that the political system will be willing to allocate resources to them. There is no particular reason to think that our community is any less capable of solving our own problems than any other community, but we need to be able to ask for the resources to do it.

Our goal, then, will be to distribute this report as widely as possible and suggest that it form the basis of some discussion in the Ward that would lead to a round of priority setting and then a round of lobbying various levels of government for resources.

Another point, which we discovered in our consultations, is that the presence of strong and respected institutions around which people can gather is a basic element of community building.

We were concerned, therefore, to discover that some of the central community institutions in the West End of Ottawa are increasingly constrained in their ability to serve the community.

The prime example of this is Pinecrest-Queensway Health and Community Services. PQHCS is a key institution in the west end of Ottawa. One way or another, its programs touch on virtually all the social issues which were raised by various members of the community during this consultation process.

We were told, however, that it is an institution under pressure, and that this pressure has a major impact on its ability to deliver programs.

In fact, each of the major programs offered by PQHCS is now functioning at capacity, compromising the ability of the institution to cope at a time when the need for its services is actually growing quite rapidly.

The most recent strategic plan noted that PQHCS catchment area has a higher than average number of children on low income; a higher than average number of seniors; a higher than average number of lone parent families; a higher than average number of residents on low income and living on government transfer income and a lower than average number of households reporting employment income. Meanwhile, the rate of increase in new Canadian populations in the catchment area is currently the highest since the early 1990s, and this on top of an existing population with above average numbers of new arrivals, with a variety of health, employment and social issues.

Pressures on PQHCS include a change in the structure of funding and grants in recent years, resulting in more that projects are unstable or short term.[3]

But pressures also

include those that come from the community – paradoxically putting pressure on

the organization precisely at a time when its services are needed most. These include a significant increase in the

number of walk in clients with immediate counselling and support needs clearly

related to housing and economic issues; an increased number of clients with

mental health issues requiring long term services, and more pressures to

respond to mental health emergencies on a 24/7 basis; an increase in the need

for eviction prevention and housing support services; more demand for counselling

for children’s groups and in schools; increases in parents struggling to

maintain jobs and parenting roles in stressful circumstances; increased

anxiety, stress and depression among job seekers, especially in the immigrant

community; changes in ODSP and Ontario Works programs; and a lack of ongoing

funding for community programs.

4.

We recommend that the City take steps to ensure core funding for

community health & resource centers like Pinecrest-Queensway Health &

Community Services is stable and sustainable, through the enhancement of

funding.

5.

We recommend that the City re-instate its Community Project Funding

program for short-term initiatives to meet emerging needs in the community.

On safety and security issues, we heard from a number of community members that these issues are an increasingly pressing concern for many members of the community, particularly in some specific neighbourhoods.

We should note that nobody who raised safety and security issues defined it as simply a crime or policing issue. Every person who spoke to us about this issue noted that early intervention, in the schools particularly, is an important way of dealing with safety issues. Everyone we spoke to told us that it is a broader issue that speaks directly to the need for community development, attention to youth at risk and the creation of recreational, educational and social development infrastructure in the community.

To a certain extent this has already begun in Bay Ward, through the activities conducted by Pinecrest-Queensway Health & Community Services, the community houses, and the establishment of the Michele Heights Youth Drop-in Centre. More initiatives like these need to be started, however, and the priority should be to locate stable and long term funding for these initiatives so that long term relationships can be developed in the community. While often these programs start as pilot projects, when proven successful it is necessary to build on these gains through establishing stable funding, or else these gains may be lost.

This does not mean that there is not a need to devote more focussed policing resources to some parts of the Ward. The Ottawa Police already have a number of programs in place to deal with issues related to youth crime, street violence, and our recommendation is that those which are most appropriate to the Ward should be adequately resourced and made permanent. However, there should be mechanisms in place to help communities to develop local crime prevention initiatives, in co-operation with partner agencies.

6.

We recommend that the City examine models of Crime Prevention

Centres in order to provide a center of expertise to assist communities in

developing the appropriate local strategy in crime prevention.

Our reading of the crime statistics (see Appendix) tells us that, overall, the crime situation is not getting worse in the Ward, but that there are hot spots that need attention.

We are aware, however, that at the national level and at the local level, people’s fear of crime can be an important factor in their lives that both restricts their activities and makes community building more difficult. For example, seniors have a higher perception of safety concerns than do the rest of the population. However, crime prevention through early intervention and community development is very well recognized by both police services and social workers as the most effective deployment of resources.

However, a few concerns were raised in the

Task Force hearings about how the Ottawa police are able to work with the

community in dealing with safety and security issues. Conversely, complacency

by the public hinders the effective use of such crime prevention programs as

Neighbourhood Watch.

We also heard that, given Bay Ward’s growing cultural diversity, cultural stereotypes and mis-perceptions were a growing concern. The view expressed at our public hearings was that the Ottawa Police Services should take the time to become more culturally sensitive and seek to break down barriers to communication and trust.

7.

We recommend that the Ottawa Police Services strengthen its current

program of cultural awareness sessions for officers and strengthen linkages to

multicultural communities, such as by taking time to talk to kids hanging

around, and break stereotypes.

As well, residents in Ottawa Community Housing neighbourhoods expressed dissatisfaction with how safety and security issues were being dealt with by Ottawa Community Housing authorities and the police. What is apparent here is the need for collaborative strategies to enable and empower these residents to work co-operatively with both OCHC staff and the police in dealing with these problems.

8.

We recommend that Ottawa Community Housing work co-operatively with

OCHC tenant groups and the police to develop collaborative strategies to

respond to safety and security issues.

Lastly, while clearly more investment in

early intervention and community development will reduce anti-social behaviour,

it must be recognized that given the existence of risk factors such as youth,

poverty and lack of education, there will be instances where youth will run

afoul of the law. While we believe that actions should have consequences, we

were attracted to restorative justice programs such as Youth in Conflict

with the Law, which is being piloted at Caldwell, a large social housing

community. We would like to support such programs as being more effective in

helping young offenders to understand the consequences of their actions and

avoid re-offending.

9.

We recommend that the City, in partnership with the Ottawa Police

Services, review the effectiveness of “Youth in Conflict with the Law”

restorative justice project in order to evaluate its broader application in the

community.

Seniors issues are particularly important in Bay Ward, given its high concentration of seniors living in our communities. We were told that seniors require help with transportation, better access to health care and other social services, and improvements to home care that is currently not being adequately met in our community.

We were also told that these issues are, at heart, resourcing issues - not enough funding for the agencies that serve seniors, which means that they can’t get the services they need at prices they can afford. It is also an incomes issue for low income seniors, who are a significant part of the seniors population in Bay Ward.

Some of these issues – transportation, for

instance – are City issues, while others – the level of social support payments

and government transfers, are a responsibility of other levels of government

that we can nonetheless lobby them on.

Another specific issue which we were made aware of is the adequacy of programs in Ottawa Community Housing for people with a range of issues, including seniors. At 2651 Regina (an OCH building), for instance, we were told that Ottawa Community Housing and/or the City need to find resources to provide a full time staff position to meet the needs of tenants, elderly and otherwise, and that it will be important that mental health support is among the services that such a full time staff person should provide. This is an area where the resources simply have to be found, because the need is so great.

The problems of seniors in our Ward are complicated both by the fact that there is such a large concentration in one Ward, and social services and agencies are not always close by and accessible, and by the fact that a growing number are multicultural seniors who have special needs that are not necessarily met by our local agencies. The result is often physical or psychological isolation, problems for which we simply must find the resources since they touch so many people in the Ward.

A recent needs

assessment by Pinecrest-Queensway Health & Community Services sheds some

light on both of these issues, and this is corroborated by the experience of

staff at Olde Forge Community Resource Centre.

The needs assessment identified issues of safety and security as concerns for isolated seniors. Their isolation is intensified by the fact that lack of funds makes it difficult for them to join any activities or obtain and services that have a cost or fee. Transportation issues make it difficult to get to activities outside their building, as most do not have access to a vehicle and taxis are too expensive; moreover, most seniors are reluctant to use OC Transpo after dark. Health issues are also a major concern and most have only limited access to follow up health care, especially those who do not have family or friends as supporters.

Most of the measures identified as addressing the issues of isolated seniors are not expensive, but they would clearly require additional resources. They include bringing more services to the buildings where seniors live and addressing the cost of fees and other barriers to services, as well as setting up programs to raise awareness among isolated seniors of the programs available for them in the community. Addressing these issues, and finding the necessary resources, is a priority.

10.

We recommend that the City develop, in collaboration with its partner

agencies, a strategy to meet the growing needs of our aging population.

11.

We recommend that the City expand the Council on Aging’s “Viellir chez

soi – Aging in Place” model, which co-ordinates services for seniors in seniors

buildings to help them age in place, including home care, home support, and

mental health services. The obvious location for this expansion would be in Bay

Ward.

12.

We recommend that the City develop, in collaboration with its partner

agencies, a transportation program that will better enable seniors to gain

access to both social and recreational activities that are necessary for their

healthy living.

The PQHCS needs assessment for multicultural seniors also identified transportation as a major issue, since many ethnic seniors don’t drive and are fearful of using the public transit system. As expected, the needs assessment identified language as a barrier to accessing many programs and services. Most multicultural seniors feel only poorly connected with their community and very few report being involved in any community activities.

As with

isolated seniors, most of the measures identified as addressing the needs of

multicultural seniors are not expensive, but would clearly require some

additional resources. They include some

way of raising awareness among multicultural seniors of the programs that are

available for them, and volunteers in the community to act as go-betweens on

government and community services, especially with respect to translation

services. As with seniors in general, a

place to go to socialize was mentioned by virtually all who participated in the

PQHCS needs assessment as a highly desirable thing, and was likewise identified

in the Task Force public hearings. The

possible closure or relocation of the Alex Dayton Seniors Centre at Carlingwood

Mall may further strain the resources available in the community to deal with

this problem. The Owls Nest, an

initiative of the former Region, was a highly successful example of a program

that met real needs, and our recommendation is that something of this sort

should be set up again, with stable funding.

13.

We recommend that resources be identified to set up one or more meeting

places in Bay Ward where seniors can go, to get their social needs met, to

access basic information they need, and where they can build networks of

support both among themselves and with volunteers and others in the community.

14.

We recommend that the City take steps to ensure that funding for

programs to support seniors, such as Olde Forge Community Resource Centre and

Nepean Seniors Home Support, are stable and sustainable, through the use of

core-funding programs.

We were told by pretty well everyone we talked to that programs to address issues faced by young people in Bay Ward are woefully inadequate. This may be the only area in which there was virtual unanimity among all those we talked to. The lack in programming includes early intervention programs, sports and recreation programs for older youth, as well as leadership training, skills development and employment readiness programs.

We were told that interesting programs in each of these areas do exist in the Ward, but that each is threatened by short term unstable funding that does not allow the building of long term relationships in the community.

The Youth Makes It Happen program,

for instance, was considered a success by everyone we talked to, but its short

term funding base was inadequate to allow it to continue on a long term basis.

15.

We recommend that the City provide funding for full-time youth outreach

workers, to work with high-risk youth in the Foster Farm, Britannia Woods,

Michele Heights and Bayshore areas to develop appropriate social and

recreational activities, including leadership development and mentoring. These

youth outreach workers should work where appropriate with such resources as the

Foster Farm and Michele Heights Community Centres, the community houses,

Pinecrest-Queensway youth outreach activities, and with Bayshore facilities.

16.

We recommend that, similar to the highly successful “Success by Six”

program that provides the supports to children to successfully reach school,

that a program be developed between schools, social service agencies, the

Children’s Aid Society and Public Health, to identify and support children at

risk in their elementary school years.

Similarly, employment readiness programs like Pinecrest Queensway’s Retail Program have been pronounced a success by everyone who we talked to. These programs need stable funding, and they need to be extended both in geographic scope (offered in more places) available to more youth, and extended to more types of employment. More employers should be encouraged to participate.

The principle here is that programs have to be close to home and sustainable to build relationships. Although the City is only one of the players in this area, we agree that more funding is needed, that the funding base of many youth programs has to be made stable and long term, and that more people need to be exposed to these kinds of programs.

For us the issue is straightforward: in a rapidly changing multicultural community, with high unemployment, much poverty and few opportunities, the cost of waiting until later is just too high. If we decide not to fund important youth oriented programs for short term budgetary reasons we will ultimately pay more in the long run – in social terms and also in financial terms.

Ultimately the solutions to many social problems, youth problems included, lie in getting people out of the low income trap, providing them with employment opportunities and stable incomes. These are solutions that go far beyond the fiscal ability or the jurisdiction of the City, but we can lobby other levels of government for youth programs, job creation, and skills and training programs that will begin to address some of these issues.

One area that we can work on at the City level is more co-ops and internships with local employers. The City and various agencies have devoted some resources to encouraging local employers to take on youth, but these programs should be made more intensive. As a model employer, the City itself should be taking on more co-op students and interns.

17.

We recommend that the City take steps to expand job training

opportunities for youth, not only internally as a model employer, but

supporting job training programs for youth by actively recruiting more employer

participation.