REPORT

TO COMMITTEE(S) OF COUNCIL

INTERNAL ROUTING CHECKLIST

|

|

|

APPLICANT: n/a

APPLICANT’S

ADDRESS:

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Report to/Rapport au :

Planning and

Environment Committee

Comité de l'urbanisme et de l'environnement

Submitted by/Soumis par : Nancy Schepers, Deputy City Manager

Directrice municipale adjointe,

Planning,

Transit and the Environment

Urbanisme, Transport en commun et

Environnement

Contact Person/Personne-ressource : Richard Kilstrom, Manager/Gestionnaire, Community Planning and Design/Aménagement et conception communautaire,

Planning Branch/Direction de l’urbanisme

(613)

580-2424 x22653, Richard.Kilstrom@ottawa.ca

REPORT RECOMMENDATION

That the Planning and Environment Committee receive for information the White Paper on "Development in the Greenbelt" prepared as part of the consultations being carried out in association with the Official Plan, Transportation Master Plan and Infrastructure Master Plan reviews.

RECOMMANDATION DU RAPPORT

Que

le Comité de l'urbanisme et de l'environnement prenne connaissance du livre

blanc sur « l'Aménagement dans la ceinture de verdure » rédigé dans

le cadre des consultations effectuées en lien avec l'examen du Plan officiel,

du Plan directeur des transports et du Plan directeur de l'infrastructure

BACKGROUND

As part of the 2008 review of the Official Plan and the Transportation and Infrastructure Master Plans a series of White Papers is being produced to engage Councillors and the community in debate on important issues. This latest White Paper, discussing the pros and cons of possibly developing limited areas of the Greenbelt, is part of that series. As with other White Papers, the report does not take a position, it simply provides some basic information and asks questions in order to encourage debate and dialogue.

DISCUSSION

The Greenbelt White Paper is somewhat different from others, in that the City of Ottawa does not control development in the Greenbelt, rather, that is the jurisdiction of the National Capital Commission (NCC). However, staff are of the opinion that given the fundamental role the federal Greenbelt has in structuring the current and future form of urban development in Ottawa and the impacts it has on the City's transportation and infrastructure systems, Councillors and citizens have a unique stake in making their views on the future of the Greenbelt known to the NCC. Given that the Commission has launched a comprehensive review of its 1996 Greenbelt Master Plan and that reviews of the City's long-term plans are also underway, now is an appropriate time to think about and discuss these questions.

CONSULTATION

The White Paper will be posted on Ottawa.ca for public comment and will also be sent to residents who have “e-subscribed” to the City’s Official Plan review contact list. A summary of the consultation results will be provided to Committee and the NCC.

FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS

Funds for public consultation on the Greenbelt White Paper are available in the operating account for the Official Plan review (112730).

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION

Document 1 White Paper on Development in the Greenbelt

DISPOSITION

Planning, Transit and the Environment Department to initiate consultation on the Greenbelt White Paper.

WHITE PAPER ON DEVELOPMENT IN THE GREENBELT DOCUMENT 1

White

Paper

Development in the Greenbelt

Overview

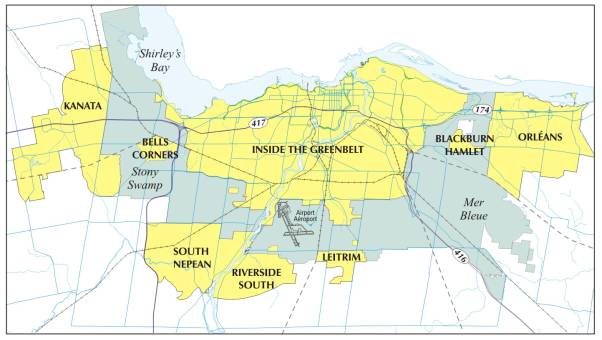

Created in the 1960s by the National Capital

Commission (NCC), the Greenbelt is a broad swath of federally owned and managed

lands that separates the centrally located portions of the City of Ottawa from

the three urban communities established in the early 1970s (Kanata, Orléans and

South Nepean /Riverside South/Leitrim).

A feature unique to Ottawa’s development

pattern, the Greenbelt remains largely undeveloped. Exceptions to this include: the Ottawa International Airport,

several clusters of research facilities, the Connaught Rifle Range, Nepean

Sportsplex, the 416 and 417 highways and City roads.

The NCC is initiating a comprehensive review of

the Greenbelt Master Plan, which will examine many issues concerning the

ongoing management of these lands in relation to the federal mandate and will

include extensive community consultation.

The City is undergoing an Official Plan Review

which, among other things, examines the need for additional land for urban

purposes. It considers whether a

discussion of urban land should include the option of some development within

the Greenbelt and it is intended that this discussion will feed into the NCC’s

review of the Greenbelt Master Plan. It should be noted that any and all

views expressed in this White Paper are those of the City of Ottawa and not

those of the National Capital Commission.

This paper examines the implications for the

potential, future development of portions of the Greenbelt, including:

A. Impact of the Greenbelt on Ottawa –

What does the Greenbelt contribute, what does it cost?

B. Development Scenarios for the Greenbelt

– What, if any, options for development should be considered?

C. Arguments for Developing Portions of the

Greenbelt – What might be gained

through development?

D. Arguments Against Developing Portions of

the Greenbelt – What might be lost?

Quick Facts

The Greenbelt occupies an area of approximately 20,800

hectares, nearly identical to the size of the urban area confined within its

inner limits and just less than one half the size of Gatineau Park.

Undeveloped portions (comprising wetlands, agricultural

land, forest, shrub and idle lands) account for approximately 85% of the total

area.

Created through land purchases and

expropriation, the cost of acquisition was approximately $40 million in 1966

dollars, a small fraction of the land value today.

Background

The completion of the 1950 Plan for the National Capital (often referred to as the Gréber

Plan) was followed by a period of land acquisition by the federal government

through the 1950s and 1960s, including lands for Gatineau Park, the Greenbelt,

federal office sites, parkway development and railway relocation.

A recommendation of the Gréber Plan, the Greenbelt was part

of an overall approach to creating a beautiful and distinctive setting for the

National Capital. It was intended to limit urban growth around Ottawa, protect

the scenic countryside and provide a home for large institutions. The federal government began acquiring land

for the Greenbelt in 1956. However, its

utility to contain urban growth in the Capital had been eclipsed by the time

its acquisition was completed. By the

early 1970s, development of the urban communities lying outside its limits

(Kanata, Barrhaven and Orleans) was well underway.

Three-quarters of the Greenbelt lands are owned and managed

by the National Capital Commission. The

rest is mainly held by other federal departments. The Greenbelt features a mix

of farms, wetlands and forests that offer a range of outdoor recreation

and learning opportunities, providing a unique rural setting for the

Capital. In addition, federal and major

research institutions that need open spaces to operate have been

located in the Greenbelt[1].

In 1985 the Neilson Task Force was struck to review options

for streamlining government and as one result the federal departments were

directed to rationalize their landholdings.

Arising from this was the concept of a “National Interest Land Mass”

(NILM) which identified lands required for the long-term support of federal

functions in the Capital. Approved by

the Treasury Board in 1998, the NILM designation included the Greenbelt lands.

In the mid 1990s, the NCC prepared several planning

exercises in relation to the NILM lands including the Greenbelt Master Plan

completed in 1996. According to the

Master Plan, the Greenbelt exists for Canadians and regional residents, an

expression of the federal government’s desire for a Capital of outstanding

character and beauty. It is a living

symbol of the rural landscapes that make up the majority of Canada’s inhabited

area and a symbol of Canada’s commitment to the stewardship of natural

resources.[2]

The statement of fundamental assumptions in the Master Plan

establishes the Greenbelt as a continuous belt of lands in public ownership, in

its present shape and location.

According to the Master Plan, the central objective of the Greenbelt is

to provide a rural setting for the

Capital, with crisp boundaries that contrast its character with the urban

areas that border it. The experience of arrival at the Capital, whether by

road, train, water or air is, by design, intended to include the experience of

moving through a rural landscape - providing a dramatic entry to and exit from

the Capital.

Supporting this central objective, the Greenbelt Master Plan

establishes policies for the use and management of Greenbelt lands that meet a range of secondary objectives,

including: accommodating a range of public activities requiring a rural or

natural environment; preserving natural ecosystems; sustaining a vibrant rural

community of productive farms and forests; and providing settings for

facilities that contribute to or benefit from the Greenbelt including a range

of accessible attractions and visitor services.

The narrow question being examined in this White Paper as

part of the City’s Official Plan review is whether the central objective of the

Greenbelt remains relevant (i.e. the preservation of a rural setting for the

Capital) and whether that objective can be achieved with a different

configuration which may include the development of portions of the Greenbelt

for urban purposes.

A. Impact of the

Greenbelt on Ottawa

According to the Greenbelt

Master Plan, the Greenbelt has “influenced the living and working patterns

of thousands of people and created an urban form that is unique in North

America”.[3] Fair enough, but influenced how? And what are the impacts of the Greenbelt on

the residents of Ottawa? In approaching

this question, there are three distinct dimensions to be examined: economic

impacts; social impacts and environmental impacts.

Economic Impact

Looking first at economics, there are two

considerations. What does the Greenbelt

“contribute” and what does it “cost”?

In examining economic contribution, it is useful to consider

several aspects. First, are there

economic activities established in the Greenbelt that can only be successful in

a Greenbelt? Second, how important is

the Greenbelt in attracting visitors (and their spending dollars) to the

city. And third, does the Greenbelt

play a significant role in helping area employers attract and retain a skilled

workforce?

On the first point, although a range of economic activities

occurs in the Greenbelt (e.g. farming, forestry, research, airport) accounting

for approximately 11,000 jobs (half attributable to activities at or near the

airport), it would be difficult to argue that any of these activities

specifically requires a Greenbelt to be successful. There are many examples of successful farms, airports and

research centres elsewhere.

In terms of tourism, no source of data has been identified

to suggest that the Greenbelt, in and of itself, draws visitors to Ottawa. The Capital receives over 7 million “person

visits” a year[4] but the

Greenbelt is rarely (if ever) identified as a specific reason for coming to the

Capital or a must see feature to be explored once the visitor arrives. What

does get mentioned frequently by visitors is an appreciation for the “greeness”

of the Capital and the proximity to nature.

While the Greenbelt is undoubtedly a component of this, so too would be

the scenic driveways, the Rideau Canal and Gatineau Park.

As a factor in labour force development, ready access to open space, nature and active outdoor

recreation is one component in the measure of a community’s “quality of

life”. Some researchers are convinced

high quality environments help employers attract and retain employees and

increase the likelihood of a region becoming a magnet for creative talent which

drives economic success[5]. In this regard, the Greenbelt is well used

(and appreciated) by area residents.

According to the NCC’s website, the Greenbelt receives over one million

visits annually and based on an examination of visitor data, it would appear

that local residents account for almost all of these visits. Although difficult

to quantify, the case for the Greenbelt’s contribution to the “quality of life”

in the Capital is perhaps the easiest to demonstrate.

Having looked briefly at economic contribution, what about

the cost of maintaining the Greenbelt?

As a result of development pressures that emerged in the

late 1960s, urban development leapfrogged beyond the limits of the

Greenbelt. What has resulted is a

fragmented urban area with three large urban communities attached to the outer

limit of the Greenbelt, separated from the inner urban area by a distance that

varies from three to eight kilometers. Because most of the jobs and major

facilities such as universities and hospitals are located in the inner urban

area, and 40% of the City’s residents now live in areas beyond the limits of

the Greenbelt, a large amount of travel is induced through the Greenbelt

largely, but not exclusively, related to the journey to work. Similarly, because water and sewage

treatment systems are centralized in the inner area, while a third of the urban

population lies beyond, the sewer and water mains to serve these populations

are of necessity made longer by the Greenbelt crossing.

As a result of development pressures that emerged in the

late 1960s, urban development leapfrogged beyond the limits of the

Greenbelt. What has resulted is a

fragmented urban area with three large urban communities attached to the outer

limit of the Greenbelt, separated from the inner urban area by a distance that

varies from three to eight kilometers. Because most of the jobs and major

facilities such as universities and hospitals are located in the inner urban

area, and 40% of the City’s residents now live in areas beyond the limits of

the Greenbelt, a large amount of travel is induced through the Greenbelt

largely, but not exclusively, related to the journey to work. Similarly, because water and sewage

treatment systems are centralized in the inner area, while a third of the urban

population lies beyond, the sewer and water mains to serve these populations

are of necessity made longer by the Greenbelt crossing.

Without question, the Greenbelt has increased the amount of

infrastructure (roads, highways, water and sewer pipes) required to serve the

urban population resulting in higher capital, operations and maintenance

costs. The Greenbelt has also increased

the overall distance travelled by the City’s residents, resulting in higher

travel costs and greater amounts of air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Although the increased cost of the Greenbelt

has not been quantified, one indicator of the magnitude of this impact can be

highlighted.

Each work day, during both “rush hours” approximately 226,000 person trips are made through the Greenbelt in private automobiles and another 38,200 by transit (both peak periods, both directions). On an annual basis, this works out to approximately 250 million person-kilometers of additional travel for just the two peak periods (equivalent to about 20,000 trips across Canada and back). In addition to the road surface that needs to be maintained (approximately 141 kilometers of Greenbelt roads to repair and keep clear of snow) this additional travel requires more fuel and vehicle maintenance, at an estimated cost to private vehicle owners of more than $60 million annually simply for extra peak period travel, and produces additional vehicle emissions. It also adds approximately $10 million annually to the City’s operating costs for buses that must travel the extra distance through the Greenbelt to serve outlying communities.

On

the other hand, Ottawa has achieved a high transit modal split through the

Greenbelt. The Greenbelt as a barrier provides limited transportation options

when compared to a continuous sprawl situation. To what extent has this influenced transportation choices and

resultant modal splits?

Social Impact

Turning to social impact, there are two dimensions that

might be explored. First is the role

the Greenbelt plays in shaping community identity. The second is the degree to which the Greenbelt contributes

directly to community life.

Municipal amalgamation notwithstanding, the urban

communities of Kanata, Barrhaven and Orleans remain physically separated from

the remainder of the urban area and this separation is a direct result of the

existence of the Greenbelt. The sense

of separation is accentuated by the sharp contrast in land use (houses on one

side of the road and fields on the other) and by the magnitude of the

separation (the Greenbelt, at most locations, takes several minutes to traverse

by vehicle even at high speed). The

breaking up of the urban area into discrete territories with recognizable

boundaries may assist in combating the “geography of nowhere”[6],

providing a physical context for community identity.

In addition, the Greenbelt contains a range of facilities

that are well used by local residents.

These facilities include 100 kilometers of trails used for skiing, snowshoeing, hiking and bird watching;

the Stony Swamp and Mer Bleue nature areas; the boat launch at Shirley’s Bay

Landing; the lock station at Black Rapids on the Rideau Canal; the campground

on Corkstown Road; several toboggan hills; and the National Capital Equestrian

Centre. These facilities are close at hand for enjoyment by many urban

residents given the central location of the Greenbelt.

Environmental Impact

An examination of the Greenbelt from the perspective of

environmental impact also has several dimensions.

The Greenbelt, through public land ownership and management,

provides protection to significant environmental features including Mer Bleue,

Stony Swamp and Shirley’s Bay and corridors for wildlife movements. Its rural

character, including the promotion of active farming, protects the long term

option of having food production close to home (a contribution to “the 100 mile

diet”) and active forestry puts a source of wood fibre close at hand.

This has to be offset, however, with the Greenbelt’s

contribution to a larger environmental footprint due to the additional travel,

and associated emissions, that is induced as residents move about the urban

area to schools, work, hospitals and entertainment.

Questions: What is your opinion? Are the Greenbelt’s economic and environmental

costs justified by its benefits?

B. Development

Scenarios for the Greenbelt

Making the best use of existing facilities and infrastructure, thereby decreasing the pressure for infrastructure expansion at the outer margins of the urban area, has been part of the City’s growth management strategy since the 1990s. The issue being explored in this White Paper is the potential for strategic development of portions of the Greenbelt as one element in the implementation of this growth management strategy.

It is instructive to examine how much of the Greenbelt might

be eligible for development consideration should the key rationale for having

the Greenbelt (i.e. provide a rural setting for the Capital) ever be

abandoned. In this regard, large

portions of the Greenbelt are occupied by uses and activities that make them

unavailable for future development, including research campuses, wetlands and

other natural areas of high environmental significance, lands impacted by

aircraft noise or lands needed to protect sensitive communications

infrastructure of the Department of National Defence, and lands with existing

buildings or transportation infrastructure.

It is instructive to examine how much of the Greenbelt might

be eligible for development consideration should the key rationale for having

the Greenbelt (i.e. provide a rural setting for the Capital) ever be

abandoned. In this regard, large

portions of the Greenbelt are occupied by uses and activities that make them

unavailable for future development, including research campuses, wetlands and

other natural areas of high environmental significance, lands impacted by

aircraft noise or lands needed to protect sensitive communications

infrastructure of the Department of National Defence, and lands with existing

buildings or transportation infrastructure.

It is estimated that of the 20,800 hectares in the

Greenbelt, at least one quarter (approximately 5,560 hectares) might be

eligible for development consideration if the Greenbelt designation was removed

and the development policies of the City’s Official Plan were applied to the

lands. This estimate assumes that lands

currently designated for agricultural and other rural activities that are

currently wedged between two adjacent urban areas would be re-designated for

urban uses; that lands impacted by noise from the airport would not be used for

residential purposes; and that lands in the sight lines of CFB Leitrim

communication facilities would remain unbuilt.

If made available for development, this potential supply of development

land in the Greenbelt could provide more than 20 years of future urban land for

both housing and employment.

There are several alternate configurations that development

in the Greenbelt might take.

3 3 1 2

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

One alternative (illustrated as “1” on the map) could be

“development corridors” to take advantage of the road, water and sewer

infrastructure that is already in place. Another alternative (shown as “2” on the map) could be several

high density, mixed use “nodes” supported by rapid transit. A third alternative (shown as “3”) might be

“nibbles” to the existing Greenbelt boundary to allow extensions of existing

neighbourhoods in order to take advantage of community infrastructure that is

close at hand (shopping, schools, street networks, etc). Each of these alternatives assumes the

preservation of all important environmental features, assumes no existing

facilities are displaced, and assumes all standard planning and development

approval procedures would be followed.

Questions: What do you think? Should we consider developing limited areas of the Greenbelt as

an alternative to building on farm land further away from the city centre?

C. Arguments for

Developing Portions of the Greenbelt

The strongest argument in favour of developing portions of

the Greenbelt is to foster “sustainable development”.

This includes making good use of infrastructure that is

already built (such as roads, sewer, water, and community facilities) before

developing new areas that require building from scratch. There are several corridors of trunk sewers,

water lines, highways and City roads and transitways passing through the

Greenbelt but there is very little development located along the frontages of

these corridors. Although there is no

tax revenue from these corridors, the tax burden of operations and maintenance

costs remains. For example, the

estimated cost to the City of the extra distance buses must travel through the

Greenbelt is close to $10 million annually.

Development pressures result in expansion at the outer margin of the

urban area where infrastructure and community facilities are scare. The alternate is to redirect development

pressures inward onto lands in the Greenbelt that are closer to existing

community facilities; a form of development potentially requiring less

expenditure for new infrastructure.

Development in the Greenbelt also has the potential of

reducing growth in vehicle trip making by increasing the ability to serve more

trips by public transit and by shortening trips - fostering a more compact form

of urban development by reducing the distance between trip origins and

destinations. Vehicle emissions would be

reduced in the process, improving air quality and cutting greenhouse gas

production.

According to a recent report by the Pembina Institute[7]

which provides a comprehensive assessment of sustainability, Ottawa scored

second out of 27 Ontario municipalities overall. However, the report notes that the Greenbelt increases both the

length and number of vehicle trips, working against investments in public

transit and policies encouraging compact development. The report also postulates that by fragmenting the urban area,

the Greenbelt may erode the free exchange of ideas between firms.

Although a small portion of the Greenbelt land is actively

used, much of the Greenbelt is not. The

portions that are actively used could remain as part of the Greenbelt, possibly

incorporated into the urban area as parks.

Lands requiring protection (sensitive environmental areas and landscape

features) could also remain as part of the Greenbelt and be reserved as

conservation areas. Areas of the

Greenbelt that are not actively used (rural scrub lands) or in certain instance

areas currently farmed but isolated from larger farming districts, could be

developed, wholly or in part. The

revenues generated in the process could be used to acquire lands for additional

park lands or conservation areas at the margins of the urban area.

As a final argument, as a public landholding the development

of the Greenbelt could be used for demonstration purposes. Canada is one of the most urbanized

countries in the world and as a nation we may have grown beyond the idea

of “a Capital in a rural setting”. Perhaps what the Greenbelt has to teach us

has more to do with delivering sustainable urban development than it has to do

with remembering our rural roots.

Questions: What do you think? If portions of the Greenbelt were developed should that

development provide something unique?

D. Arguments

Against Developing Portions of the Greenbelt

There are several arguments against developing the

Greenbelt.

The first is that the Greenbelt, by both intent and design,

must remain rural to protect the “idea” of the Capital established back in the

1950s; that is to provide a setting for the Capital that sets up a deliberate

contrast between the urban area and the rural area that lies beyond. Assuming this idea of the Capital retains

its currency, it is difficult to go half way and have the Greenbelt partially

developed, and partially not. The big

idea of the Greenbelt is that it is comprised of a wide swath of rural

landscapes surrounding the Capital (now interpreted to mean the inner urban

area). The view looking towards

Parliament through the western Greenbelt from the rise on Highway 417

illustrates this argument perfectly – the current “idea” of the Capital so well

represented in this view could disappear with the development of the

intervening lands.

The second is that the Greenbelt is currently providing

protection for critical infrastructure such as the airport (including areas on

either end of the runways that are exposed to aircraft noise), the

communications infrastructure at CFB Leitrim (including antennae fields and

line-of-site to communications satellites) and the DND training areas of the

Connaught Rifle Range. This doesn’t

mean these facilities require a Greenbelt to operate; but the Greenbelt is

supportive of their existence and facilitates their operation.

The third is that the Greenbelt breaks up the urban area

into discernable communities, separating their physical identities and

providing relief to what otherwise could become an urban continuum from

Stittsville to Orleans much like the uninterrupted conurbation along Highway

401 from Pickering to Mississauga in the Greater Toronto Area. The Greenbelt provides approximately 75

kilometers of urban/rural “edge”, a distinct feature of our development pattern

that helps establish a unique quality of place.

The fourth is that the Greenbelt provides a land reserve for

the long-term future, including requirements not yet anticipated and land for

the production of food close at hand to the entire urban population as part of

a food security initiative or the possibility of energy farming (wind, solar,

biomass).

The fifth relates to the Greenbelt being contiguous. Also looking far into the future, should the

need arise for a new form of communications / transit / energy corridor serving

all portions of the urban area, the Greenbelt could provide for this without

disrupting built neighbourhoods.

Question: What do you think?

How to Provide Input

You have until September 2008 to

send your comments on this White Paper by phone, regular mail, e-mail or by

visiting the city’s Web site.

Contact the author (Ian Cross) by phone, in writing or by

e-mail:

Community Planning and

Design Division

Planning, Transit and

the Environment Department

110 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa, ON K1P 1J1

613-580-2424 ext. 21595

ian.cross@ottawa.ca

Go to Ottawa.ca/Residents/Planning and click on the 2008 Official Plan Review page. It will direct you to our Feedback page where you can list your comments and/or fill out our survey.

If you would like to be added to our notification list,

please send your e-mail address to plan@ottawa.ca

You can keep up-to-date with all the opportunities for public input on the 2008 Official Plan review by visiting the city’s Web site at Ottawa.ca.